It gets more difficult for books to take me by surprise, as I get older. It may be down to the books I read, but I tend to find this in comics more than in prose (my generation never called them ‘graphic novels’, but this is what I’m talking about).

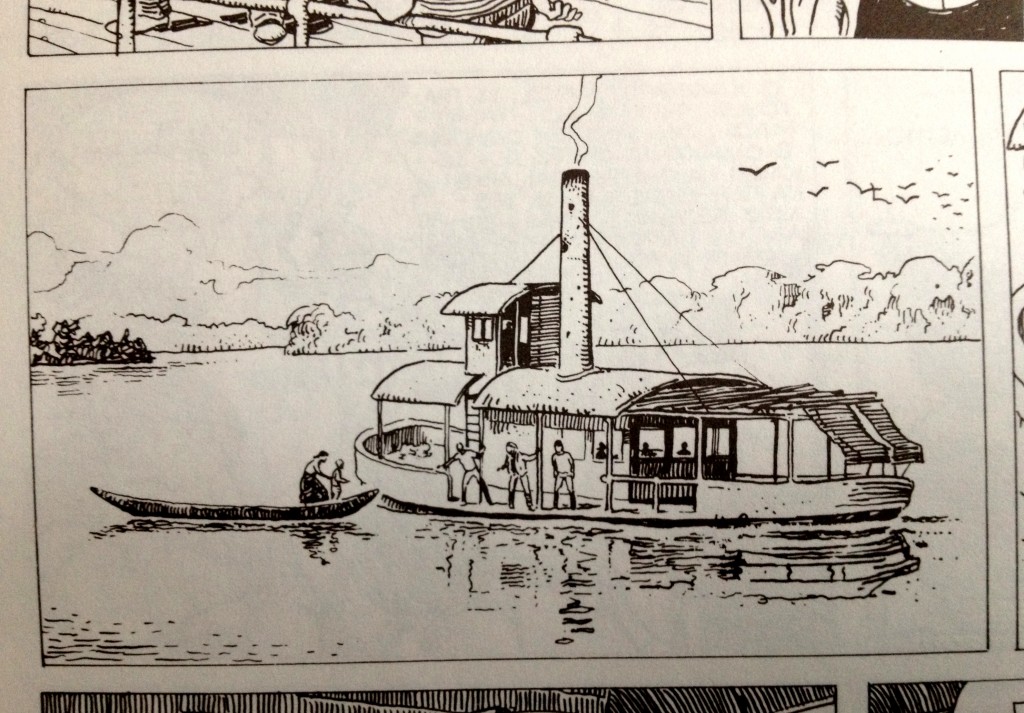

My love of comics goes back to the dawn of my literacy – the combination of story and images speaks to me very strongly. During my thirteenth year a new magazine called βαβέλ (babel) hit the newsstands in Athens, translating into Greek a knowledgeable selection of mostly European comics. Monthly instalments of anarchic, fantastical, irreverent, and sometimes profound illustrated stories held a mirror up to two deeply messed up decades, full of crises, political fluctuations, and social unrest. Post-1968 European artists had little patience for the self-absorbed, blathering demigods of 2000AD or Marvel. Instead, I got Liberatore and Tamburini’s dystopian Ranxerox, anticipating the broken down cities of Blade Runner; Édika, Gottlieb, and Lauzier, showing up the absurdities of urban middle classness; the dark, black humour of Altan and Vuillemin (still going strong); and Reiser, subversive even thirty years after his death. I balanced these with Will Eisner‘s deeply human stories, Hugo Pratt‘s languorously adventurous Corto Maltese, and Manara’s extended Bergman stories: like Corto Maltese, a man caught in a turbulent stream of fate, but dealing with his predicament rather less gracefully. (By the way, has anybody noticed that Hayao Miyazaki’s Porco Rosso is really a porcine Corto Maltese?)

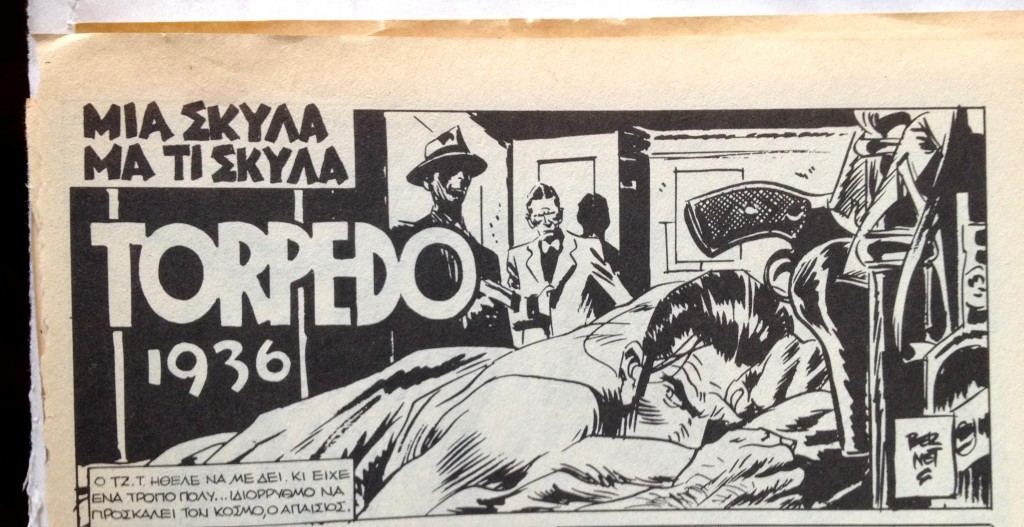

The French and Italians dominated my early collection: Giardino, Battaglia, Varenne, Saudelli, Crepax, most of them alternating between adaptations of noir story lines and wonderfully indulgent fantasies. I suspect that my love of noir literature was seeded with Abuli & Bernet’s Torpedo, and Muñoz & Sampayo’s Alack Sinner. These partnerships of superb storytellers and image-makers (Spanish and Argentinian, respectively) have superlative peers today: Darwyn Cooke’s coldly amoral Parker, an exceptional translation of Richard Stark‘s character, is rivalled for impact by Jacques Tardi’s adaptation of Manchette’s West Coast Blues. I re-read both frequently: they are masterpieces of telling a story with the least expenditure of words: only situation, and action.

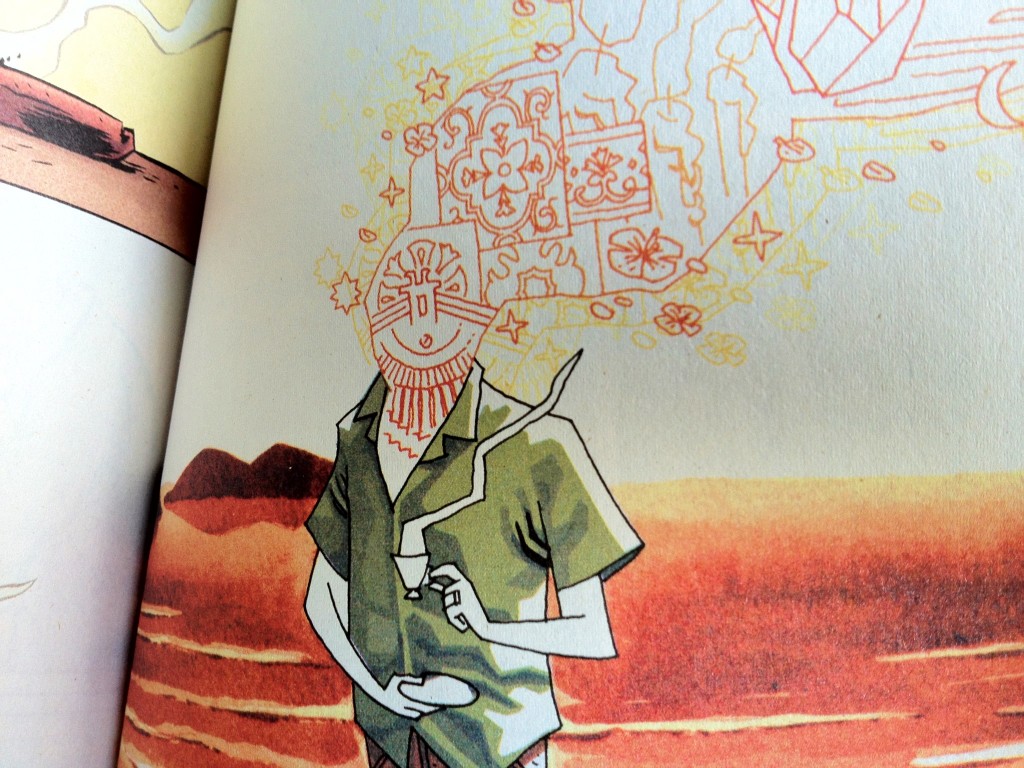

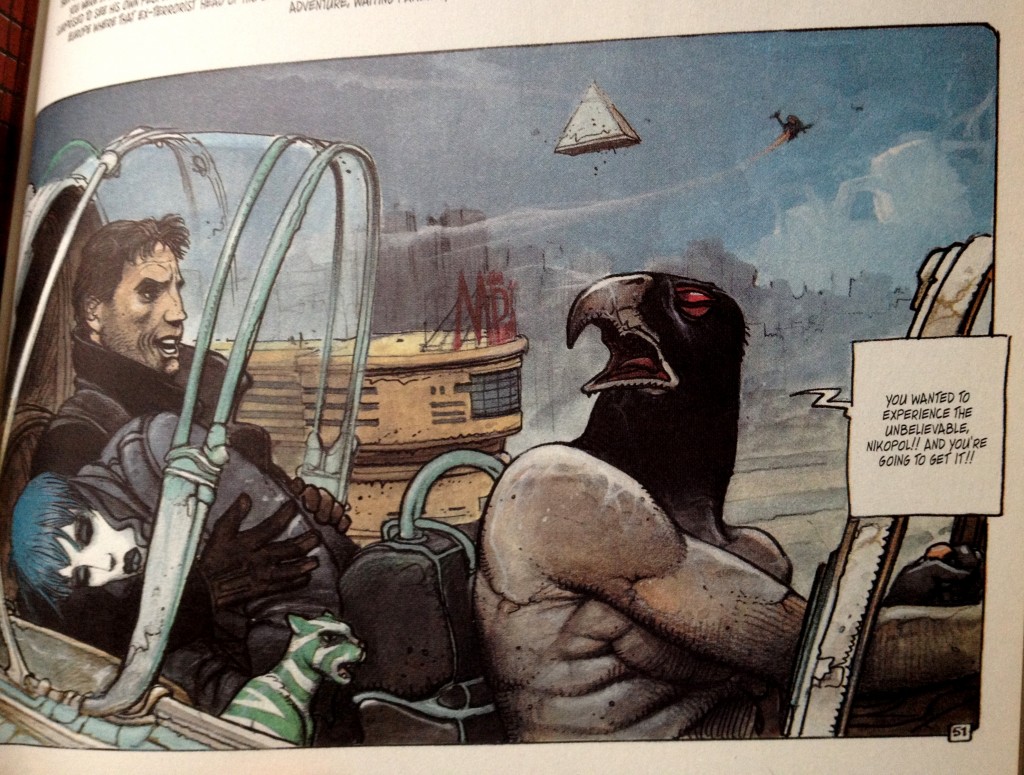

All of these stories have characters (men, mostly) in different stages of coming to terms with a world that exceeds them. In noir, the main character may have the odds stacked against him, but has perseverance, cunning, and strength to carry him forward. The most interesting stories introduce any range of character flaws, making the personalities more human. Unlike Stark’s ruthlessly efficient Parker, Andrea Pazienza‘s Zanardi is amoral in a self-destructive way, just as Moebius‘ John DiFool is a hunkering coward. By far my favourite ‘man-in-over-his-head’ character has been Pierre Christin & Enki Bilal‘s Alcide Nikopol: dislocated in time (through a bungled hibernation) and frame of reference (an Earth where ancient Egyptian gods play politics) he strives to adapt while still sucking in as much of this new world he finds himself in.

I knew Fábio Moon and Gabriel Bá from De-Tales (and Bá from The Umbrella Academy). A few days ago I got a copy of Daytripper. I started reading, and it hit me like a sledgehammer.

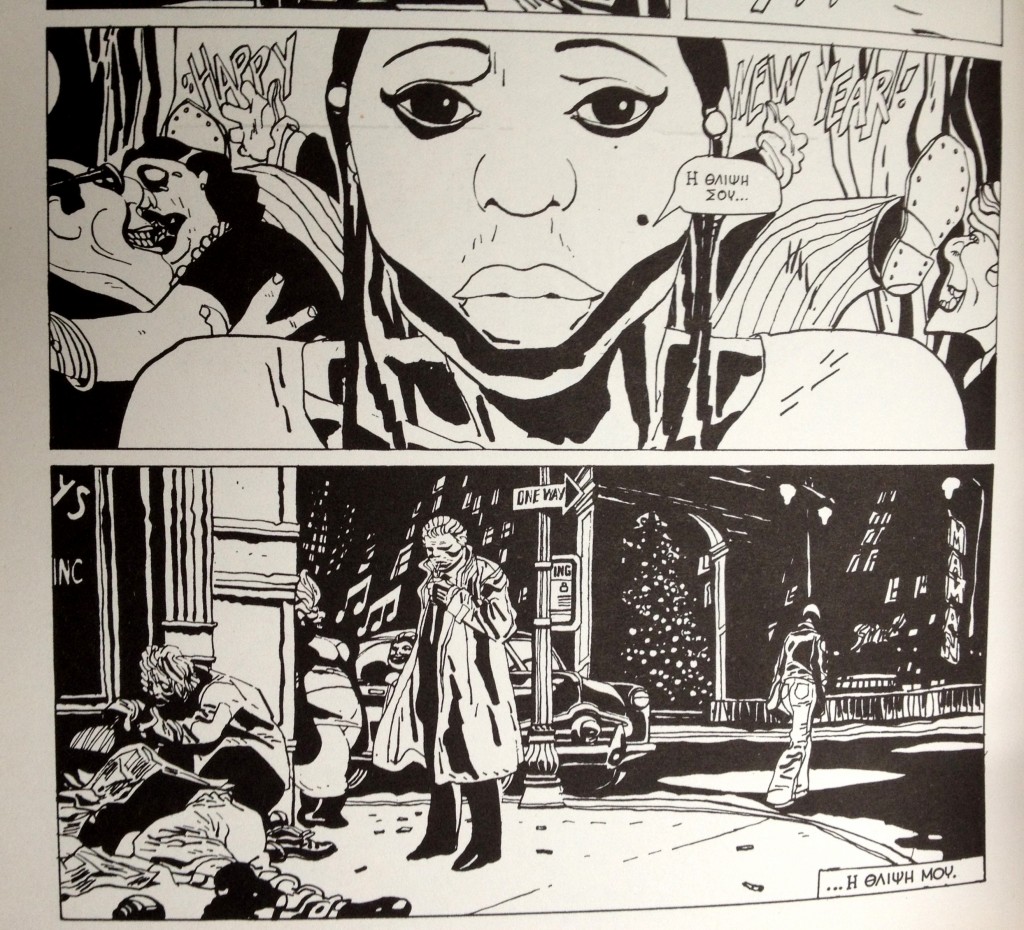

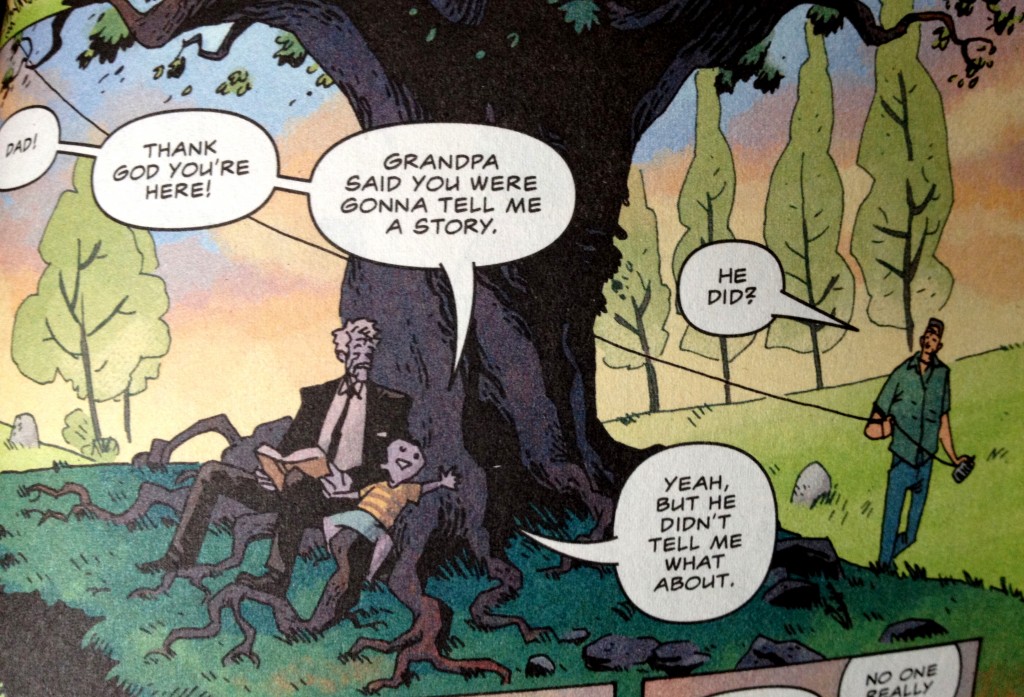

The book is about Brás, a man with ambitions to be a writer, a good father, a worthy son, and a friend. Each chapter picks one part of his life, but weaves in the storyline the unpredictability of accidents, a series of plausible ‘what ifs’ which interrupt the storyline. This is a device every Greek understands well: the Three Moirai (or Three Fates), Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos spin, apportion and cut the thread of life. (Yes, that’s the origin of the phrase.) In the Daytripper the story picks up in the next chapter, the point of interruption unknown. This wonderful device, a cross between parallel universes and a linear world, is life laid bare: a microcosm of emotions and personal, immediate relationships, within a maelstrom of unpredictability. Most will pass with little effect, some will upturn everything.

There is a lot to read in Brás’ desire for his life to exceed the limits of the immediate action and relationships. He strives to be a good friend, and father, but has deeper desires: he captures perfectly the frustration at the heart of the modern human condition, where a wider consciousness, contemplation, and ambition can place seemingly insurmountable obstructions. For most of the Daytripper, Brás embodies F Scott Fitzgerald’s famous aphorism: ‘This is what I think now: that the natural state of the sentient adult is a qualified unhappiness.’

The dialogue is economical, like reality distilled. With the excess of words removed, the force of the environment and the unspoken, imagined expressions become more powerful. And it underlines the unspoken moments, when what is not said is more powerful than paragraphs of text. This is right at the heart of the power of comics: the illustrator does not supplant the visual imagination of the reader, but fires it up and channels it in new directions. The experience of reading becomes imaginatively richer because of the presence of images.

The women in Brás’ life offer a fascinating insight into the mind of the troubled male. They are ever-present, but in the periphery; they represent the family, continuity, and the next generation, but do not share in his contemplation. Only towards the end do we see a shift: when the son has taken on the role of father himself, companionship and affection have proven a stronger constant. This is juxtaposed with the role of Jorge, Brás’ friend: stronger in intensity, alternatively present and missing, catalytic at times, but ultimately absent. The overarching feeling of solitude, the man and his thoughts alone, is accepted and embraced brilliantly at the end of a life full of people.

The Daytripper is the best example of visual poetry I have read in quite a while.