Χαζεύοντας το απολαυστικό και ταυτόχρονα εξοργιστικό This.Is.Greece. είδα την Κα Κανέλλη να ωρύεται, μεταξύ των άλλων, και για την έλλειψη γραμματοσειρών για τη σωστή γραφή της ελληνικής γλώσσας στους υπολογιστές. Υπέθεσα ότι εννούσε πολυτονική γραφή. Είπε διάφορα η Κα Κανέλλη για McDonalds και ξεπουλήματα, για τα οποία δε γνωρίζω τίποτα. Ξέρω όμως κανα-δυό πράγματα για τα πολυτονικά στους υπολογιστές. Να λοιπόν μερικές γραμματοσειρές που αξίζει να έχει υπόψη όποιος γράφει σε πολυτονικό, που είναι είτε ελεύθερες για κατέβασμα, ή έρχονται μαζί με το λειτουργικό, ή περιέχονται σε κάποιο πακέτο όπως το Microsoft Office, ή τα πακέτα της Adobe, που χρησιμοποιούνται από σχεδόν όλους στο χώρο της τυπογραφίας. Δηλαδή υπάρχει μεγάλη πιθανότητα να υπάρχουν στον υπολογιστή όποιου ασχολείται με τη γλώσσα, ή την τυπογραφική παραγωγή.

Η λίστα που δίνω δεν είναι καθόλου εξαντλητική, αλλά περιορίζεται σε γραμματοσειρές στις οποίες έβαλα το χέρι μου κι εγώ, και μπορώ να βεβαιώσω ότι αντιπροσωπεύουν σημαντική επένδυση σε έρευνα και εξέλιξη. Επίσης, είναι από έγκυρες πηγές, που σημαίνει ότι μπορούμε να έχουμε εμπιστοσύνη στην ποιότητα του λογισμικού. Εκτός από πολυτονικά Ελληνικά, οι περισσότερες καλύπτουν ευρεία Κυριλλικά, και μεγάλο εύρος του Λατινικού.

Με χρονολογική σειρά, λοιπόν, οκτώ συν μία γραμματοσειρές που μπορεί εύκολα να έχει στη διάθεσή της η Κα Κανέλλη:

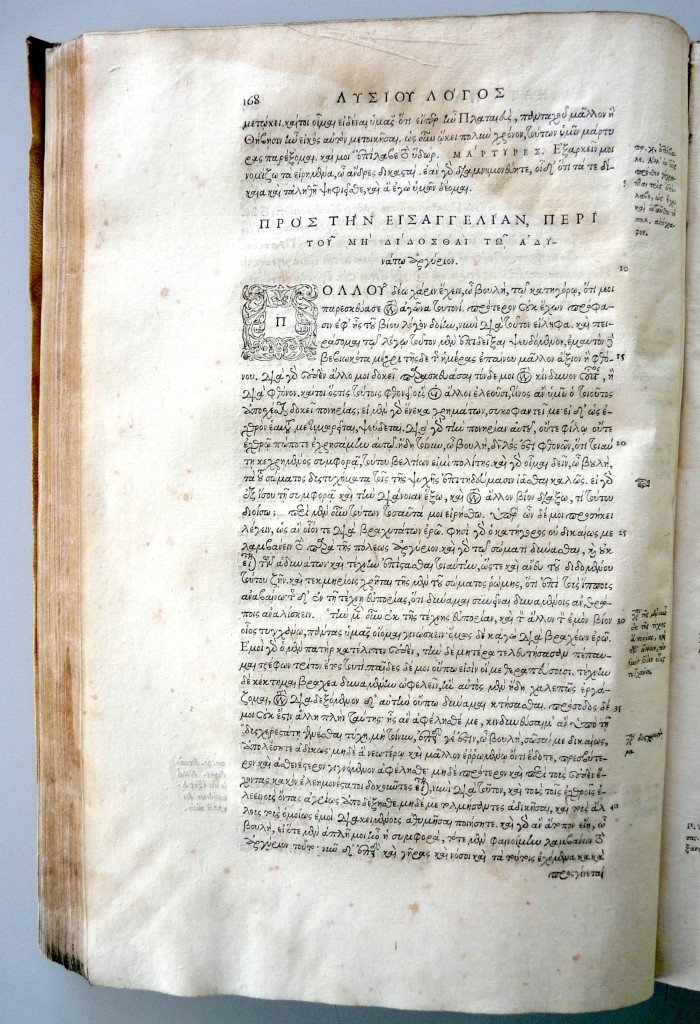

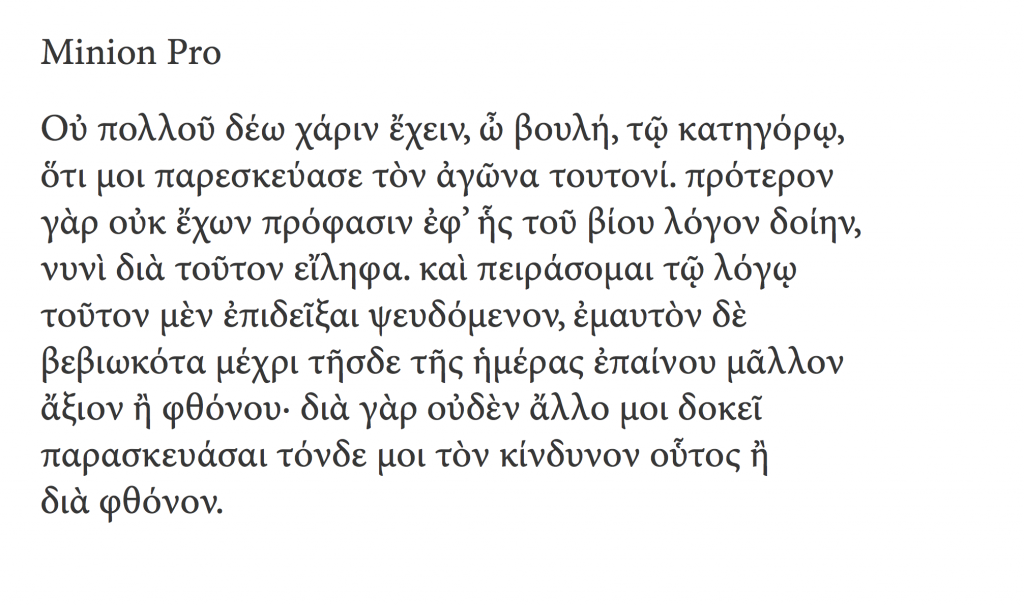

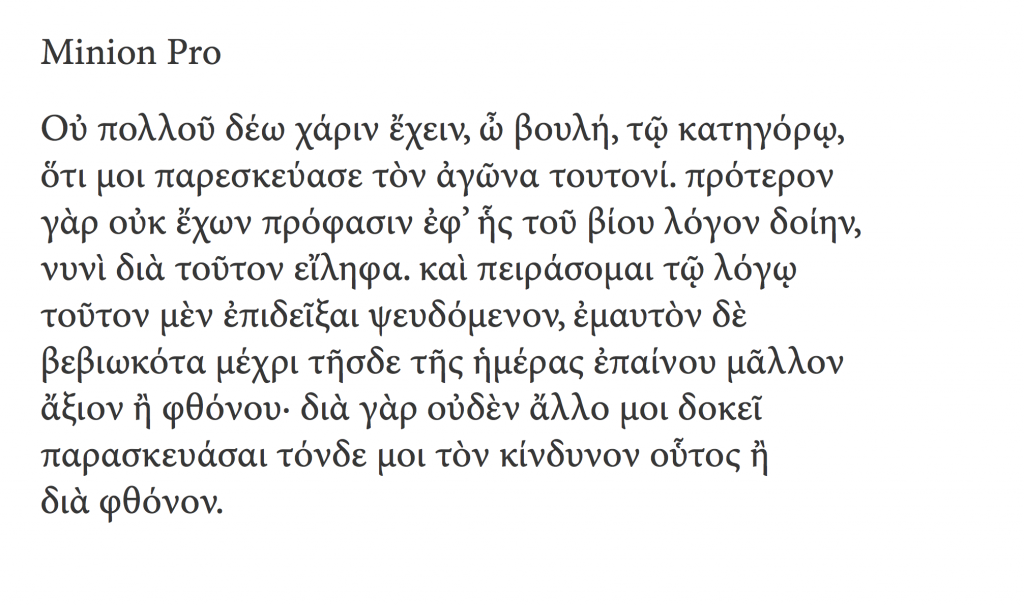

1 Adobe Minion Pro (2000)

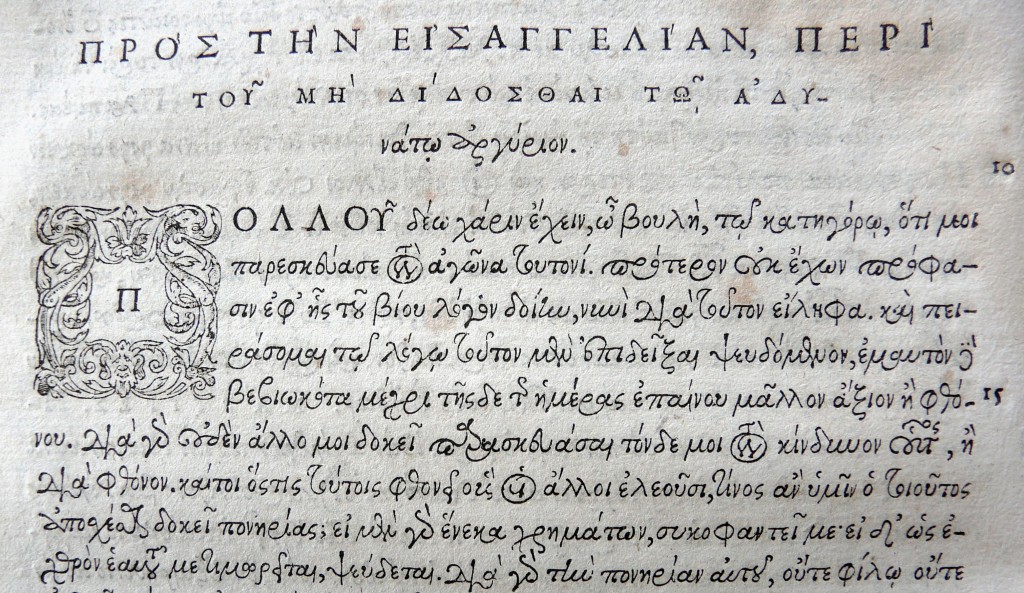

Η πρώτη σημαντική γραμματοσειρά σε πρότυπο OpenType με ουσιαστική κάλυψη του ελληνικού αλφάβητου, από τις μέρες ακόμα που το πρότυπο Unicode δεν είχε κατασταλάξει (υπάρχουν, δηλαδή, σημαντικές διαφοροποιήσεις ανάμεσα στην πρώτη και τις μετέπειτα εκδόσεις της γραμματοσειράς). Πολλά από τα βασικά ερωτήματα για την εξέλιξη και τυποποίηση των πολυτονικών ελληνικών γραμματοσειρών έγιναν μέσα από την Minion Pro, που με τη σειρά της αποτέλεσε άτυπο πρότυπο για πολλούς σχεδιαστές. Όπως σχεδόν όλες οι ιστορικές γραμματοσειρές κειμένου του Robert Slimbach, η Minion Pro προσφέρεται σε πολλές παραλλαγές βάρους και πλάτους, αλλά και τεσσάρων οπτικών μεγεθών.

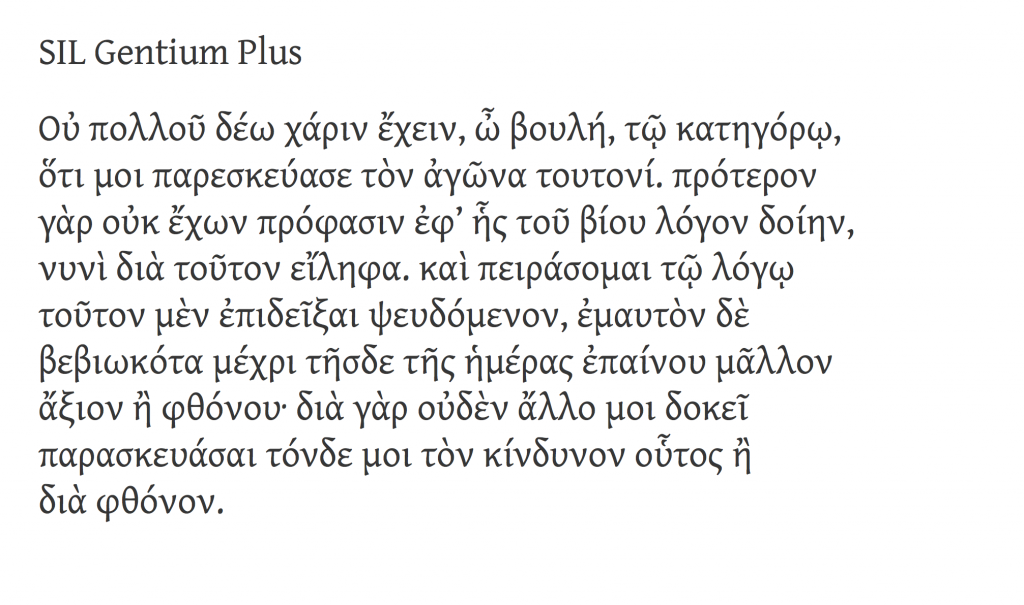

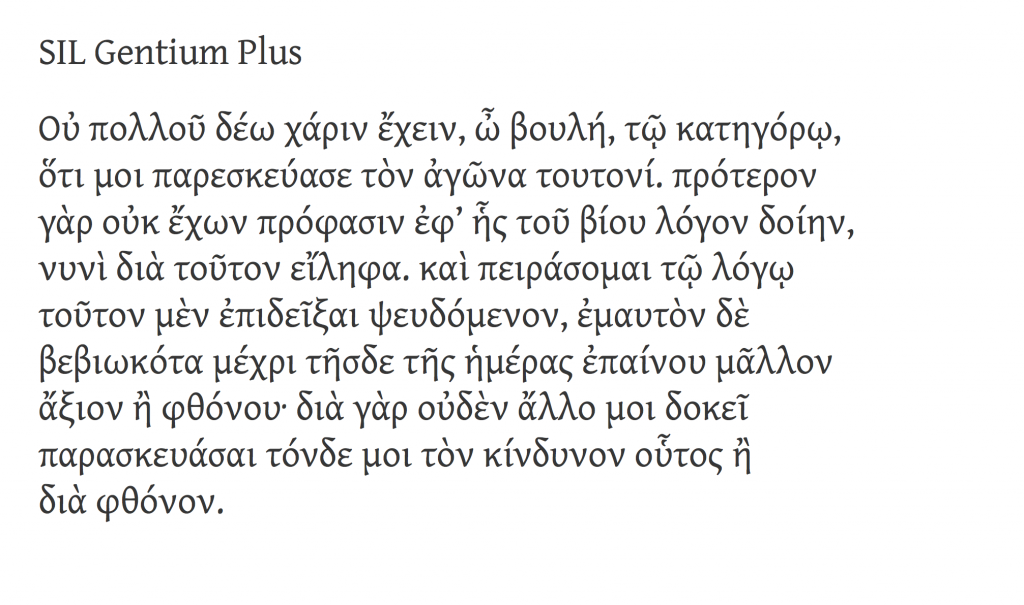

2 SIL Gentium (2003)

Μια ιδιαίτερα σημαντική γραμματοσειρά, από τις πρώτες με εκτεταμένη κάλυψη στα τρία ευρωπαϊκά αλφάβητα και πλήρη ενσωμάτωση στο πρότυπο Unicode (το λατινικό τμήμα καλύπτει μέχρι και τις Αφρικανικές γλώσσες νότια της Σαχάρας). Εξελίχθηκε από τον ήδη έμπειρο σχεδιαστή Victor Gaultney ως τμήμα των μεταπτυχιακών σπουδών στο πανεπιστήμιο του Reading, για λογαρισμό του οργανισμού SIL. Ως η πρώτη ελεύθερη Unicode γραμματοσειρά ποιότητας με πολυτονική κάλυψη, η Gentium κυριολεκτικά μεταμόρφωσε την υποστήριξη ελληνικών σε όλα τα πανεπιστήμια όπου υπάρχουν έδρες σπουδών ελληνικής γλώσσας, καθώς και τους εκδότες δίγλωσσων εκκλησιαστικών κειμένων (μια σημαντική αγορά, ειδικά στις ΗΠΑ). Δεν είναι υπερβολή να πούμε ότι δεν υπάρχει πανεπιστήμιο εκτός Ελλάδος που να μην έχει εγκατεστημένη αυτή τη γραμματοσειρά. Διατίθεται ελεύθερα από αυτή τη σελίδα.

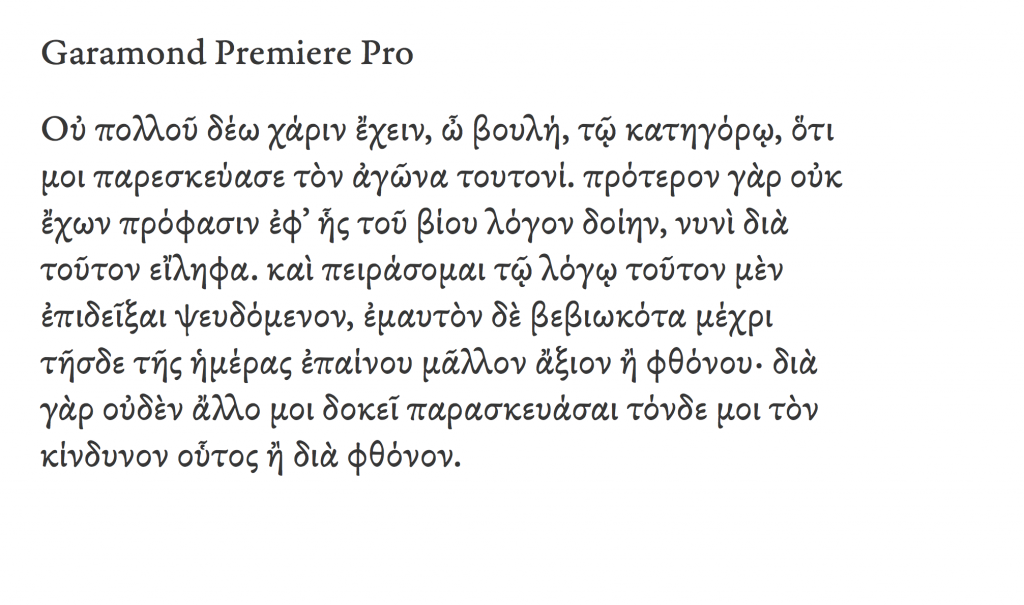

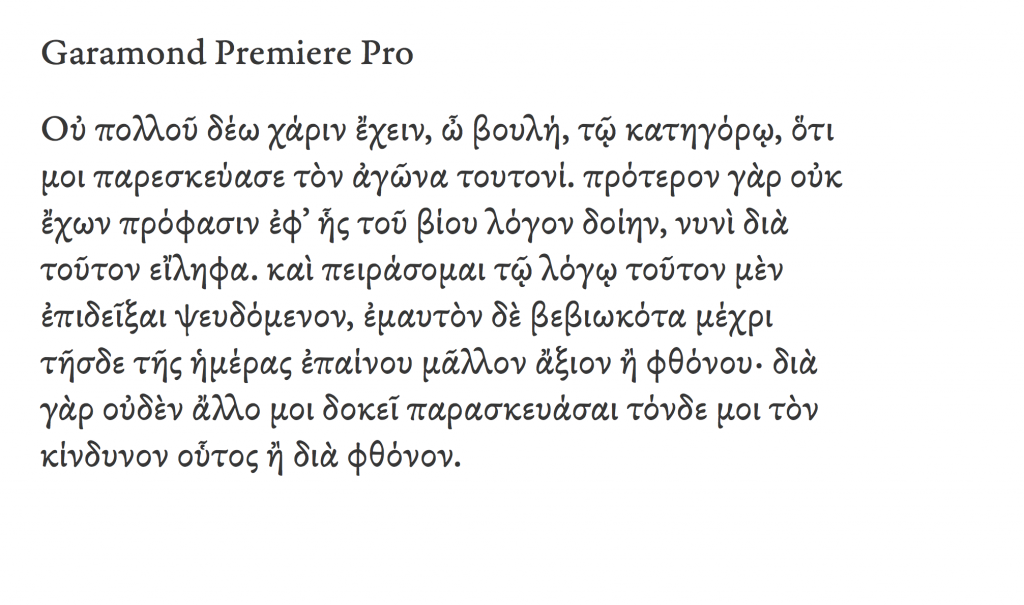

3 Adobe Garamond Premier Pro (2005)

Ενώ η Minion Pro είχε λειτουργικό λόγο ύπαρξης, και σαν τετοια είναι πιο συντηρητικά σχεδιασμένη, η Garamond Premier Pro (GPP) αποσκοπούσε στο να αναθεωρήσει τα δεδομένα των γραμματοσειρών κειμένου (μην ξεχνάμε ότι την εποχή που η GPP έπαιρνε το πράσινο φως οι περισσότεροι σχεδιαστές χρησιμοποιούσαν ακόμα μια πλημμύρα από Type 1 γραμματοσειρές με 8-μπιτες συνθέσεις χαρακτήρων: τα πρώτα δοκίμια που είδα, ήδη αρκετά αναπτυγμένα, ήταν το 2003). Η γραμματοσειρά επέστρεψε στις ονομαστικές της ιστορικές ρίζες (δηλαδή τα ελληνικά γράμματα του Garamond και του Granjon) αλλά είναι ξεκάθαρα εηρεασμένη από τα μετέπειτα ελληνικά γράμματα του Didot — και ορθά, αφού απευθύνεται στο σύγχρονο αναγνωστικό κοινό. Πάνω από όλα όμως είναι η γραμματοσειρά που έδειξε ότι η ιστορική ελληνική τυπογραφία μπορεί να εμπνεύσει αξιόλογες νέες δουλειές, που δουλεύουν πολύ καλά σε ρέοντα κείμενα. Και αυτή έχει πλήθος παραλλαγών στα βάρη.

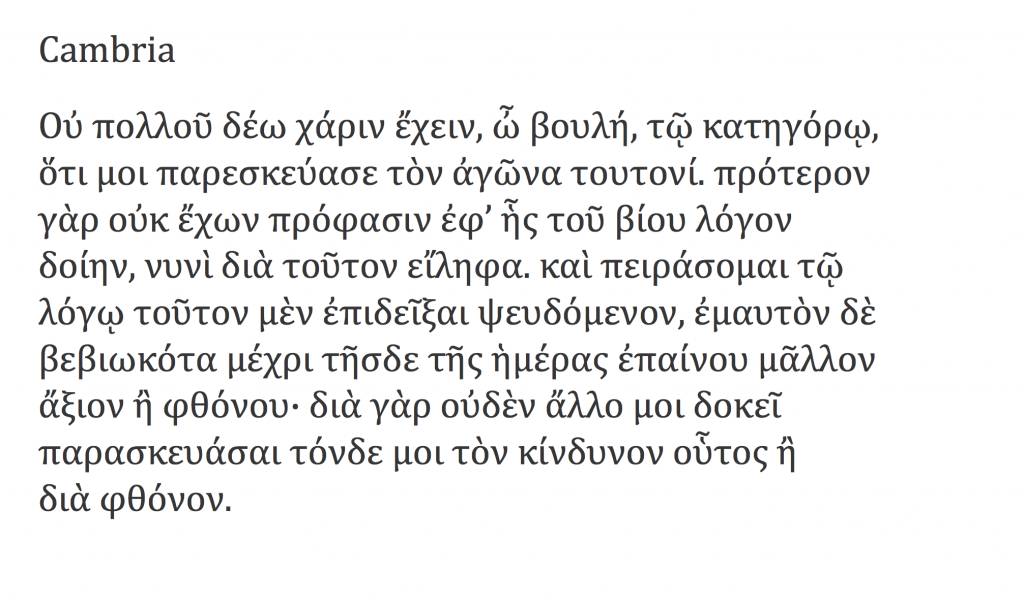

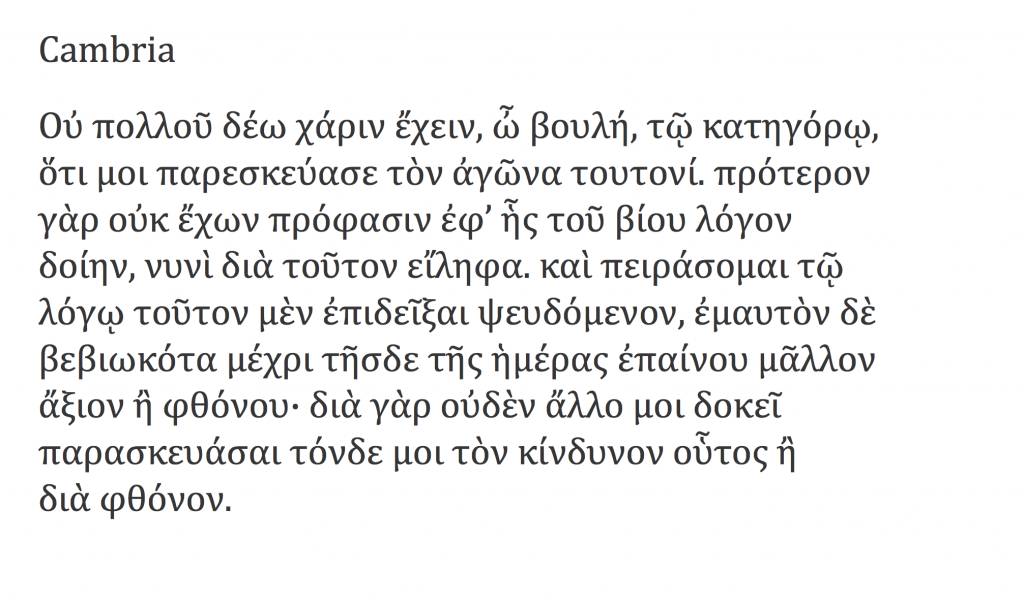

4 Microsoft CT Cambria (2007)

Αν και διατέθηκαν το 2007, οι γραμματοσειρές της Microsoft ήταν έτοιμες σχεδιαστικά ήδη από το 2004. Το σύνολο του προγράμματος αποτελεί αξιοσημείωτο έργο, καθώς είναι η πρώτη φορά που τα τρία βασικά αλφάβητα σχεδιάστηκαν παράλληλα, αντί οι ελληνικοί και κυριλλικοί χαρακτήρες να ακολουθήσουν τους λατινικούς. Όταν η Cambria επιλέχτηκε για να εξελιχτεί σαν βασική γραμματοσειρά «εργασίας» προστέθηκαν εκτεταμένα πολυτονικά, αλλά και μαθηματικοί χαρακτήρες. Οι γραμματοσειρές ClearType είναι σχεδόν παντού: υπάρχουν σε κάθε υπολογιστή με σύγχρονο λειτουργικό Windows, κάθε υπολογιστή ανεξαρτήτως λειτουργικου με σύγχρονο Office, ή οποιονδήποτε υπολογιστή έχει εγκατεστημένο το PowerPoint Viewer (που διατίθεται ελεύθερα).

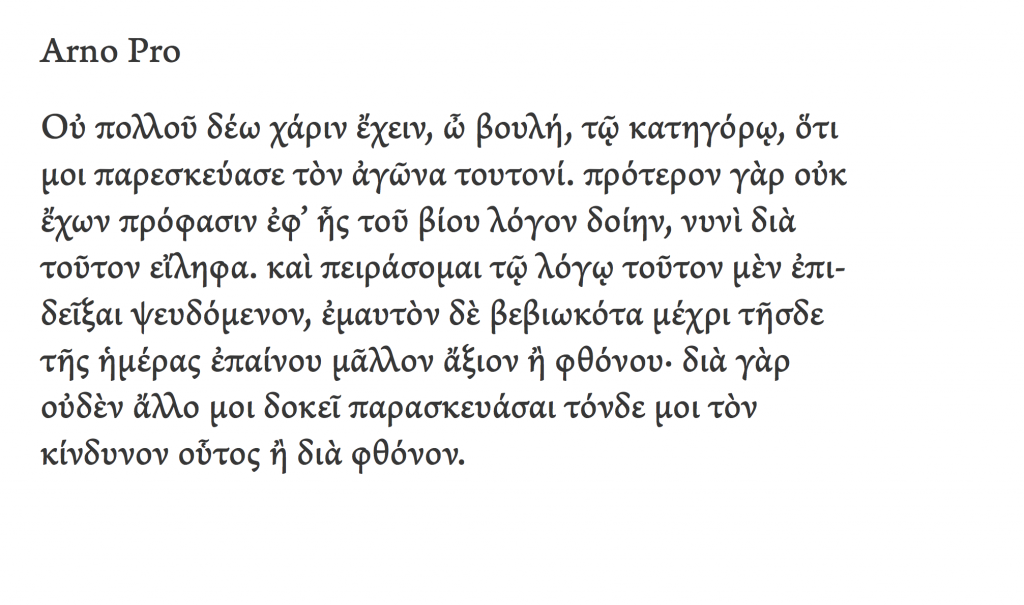

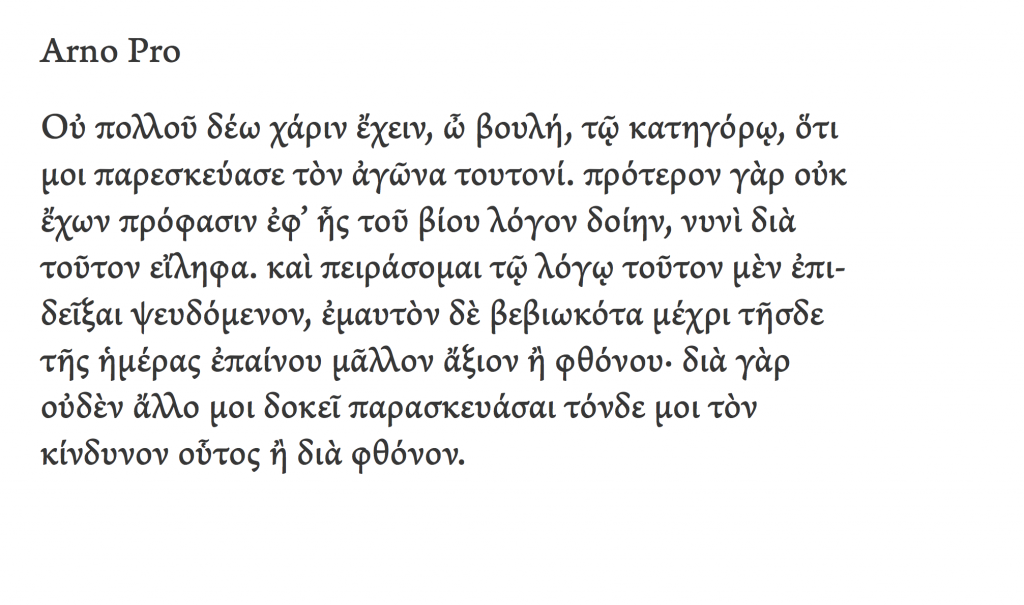

5 Arno Pro (2007)

H Arno Pro, σχεδιαστικά ανάμεσα στη Minion Pro και την GPP, χρησιμοποιείται εκτεταμένα σε εκδόσεις τόσο με ρέοντα κείμενα, όσο και σε ειδικές εκδόσεις όπως τα λεξικά, οι γλωσσολογικές μελέτες, και οι δίγλωσσες εκδόσεις. Όπως και οι υπόλοιπες γραμματοσειρές κειμένου της Adobe, η πλήρης οικογένεια έχει πολλές παραλλαγές βάρους και εύρους.

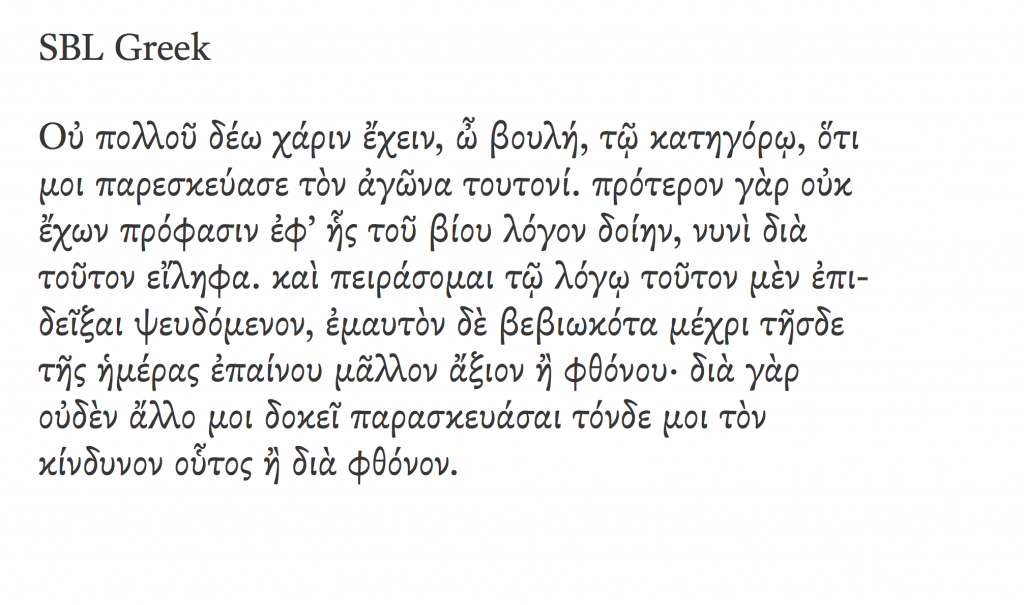

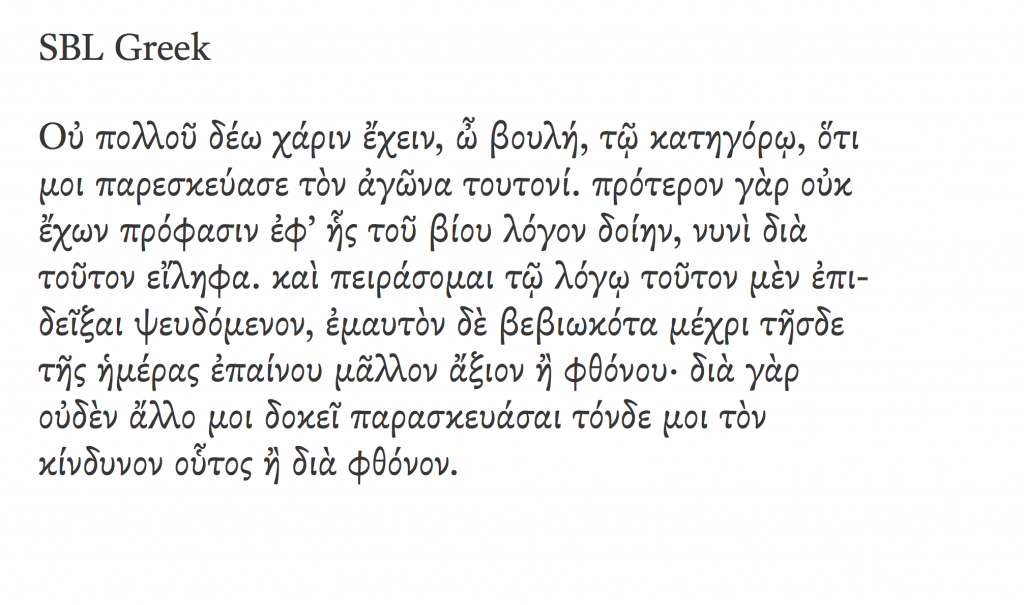

6 SBL Greek (2009)

Μία ιδιαίτερα όμορφη γραμματοσειρά, πιθανότατα η καλύτερη ενημέρωση του ιστορικού μοντέλου του Didot (από τον John Hudson, σχεδιαστή με μακρά ενασχόληση με την ελληνική τυπογραφία). Η γραμματοσειρά έχει ίσως το πιο εκτεταμένο σύνολο χαρακτήρων για Ελληνικά κείμενα που μπορεί κανείς να βρει στην αγορά: έχει σχεδιαστεί με κριτήριο τις ανάγκες των μελετητών της Γραφής, και σαν τέτοια καλύπτει και ανάγκες πολλών συγγενών επιστημών (π.χ. παλαιογραφία). Το «πρόβλημα» βέβαια είναι ότι ως γραμματοσειρά μεταγραφής χειρόγραφων δεν παρέχει παρά ένα βάρος. Διατίθεται ελεύθερα από αυτή τη σελίδα.

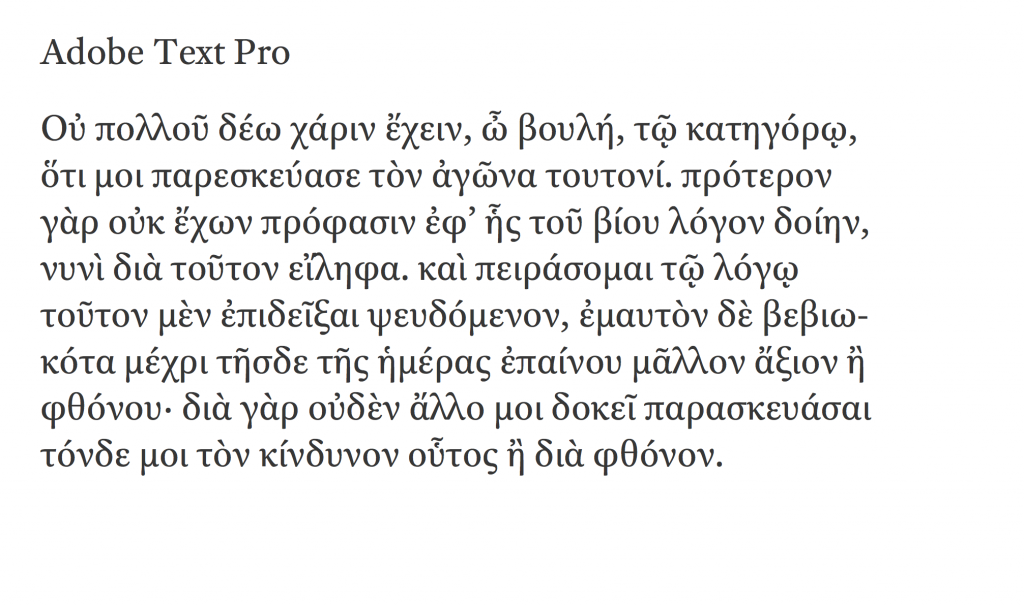

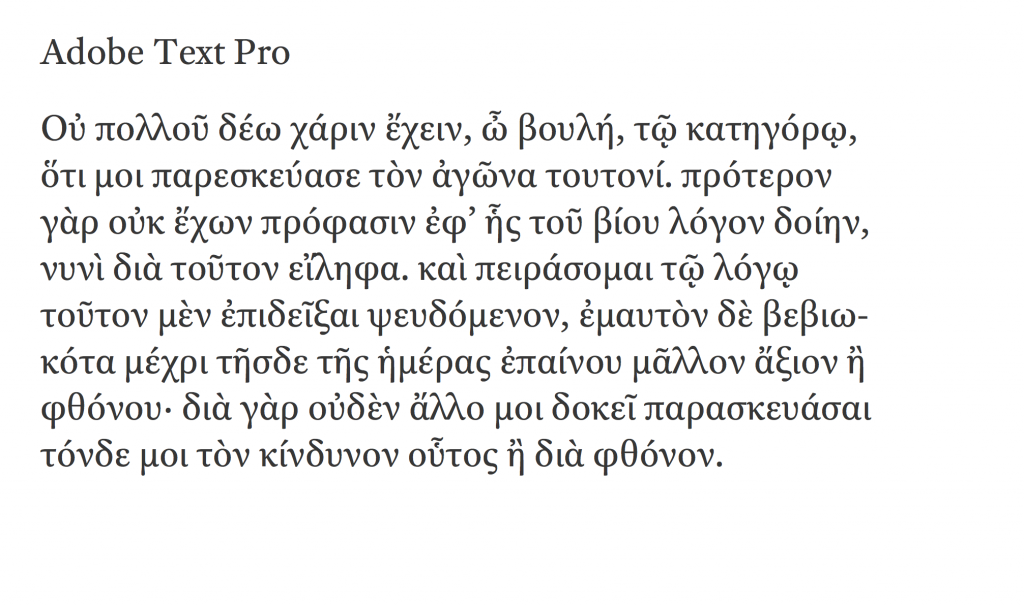

7 Adobe Text Pro (2010)

Μια γραμματοσειρά με έξι μόνο μέλη (τρία βάρη, συν τα πλάγιά τους) αλλά σύγχρονη σχεδιαστική προσέγγιση στο σύνολο των χαρακτήρων, και στην εμφάνισή της στην οθόνη και τις εκτυπώσεις, κατάλληλη για κείμενα όπου το πλήθος των παραλλαγών είναι περιττό. Ο,τιδήποτε έκανε κάποιος παλαιότερα με την μετριότατη Times Greek, μπορεί να κάνει πολύ καλύτερα με την Adobe Text.

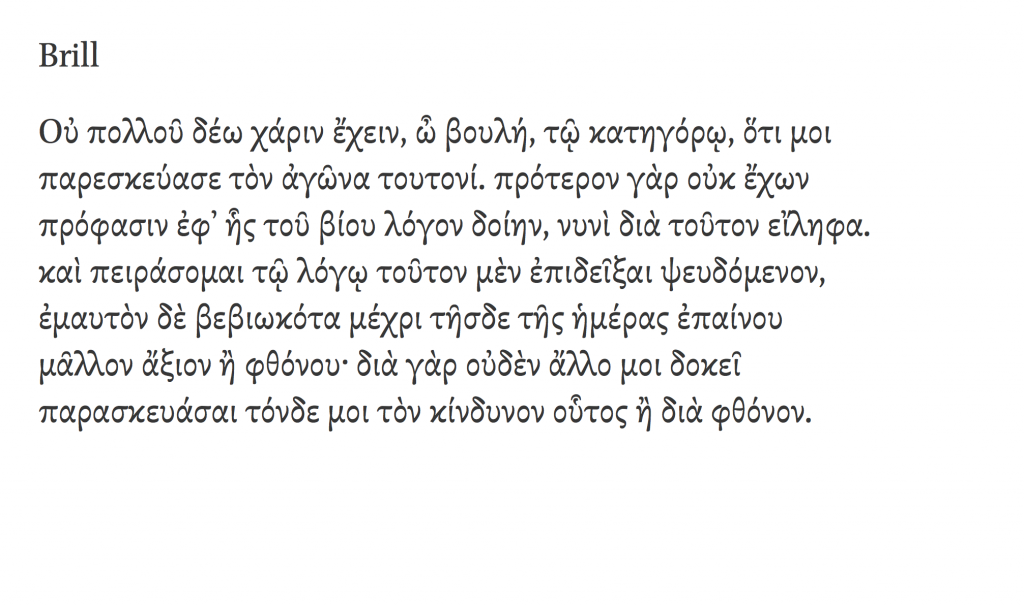

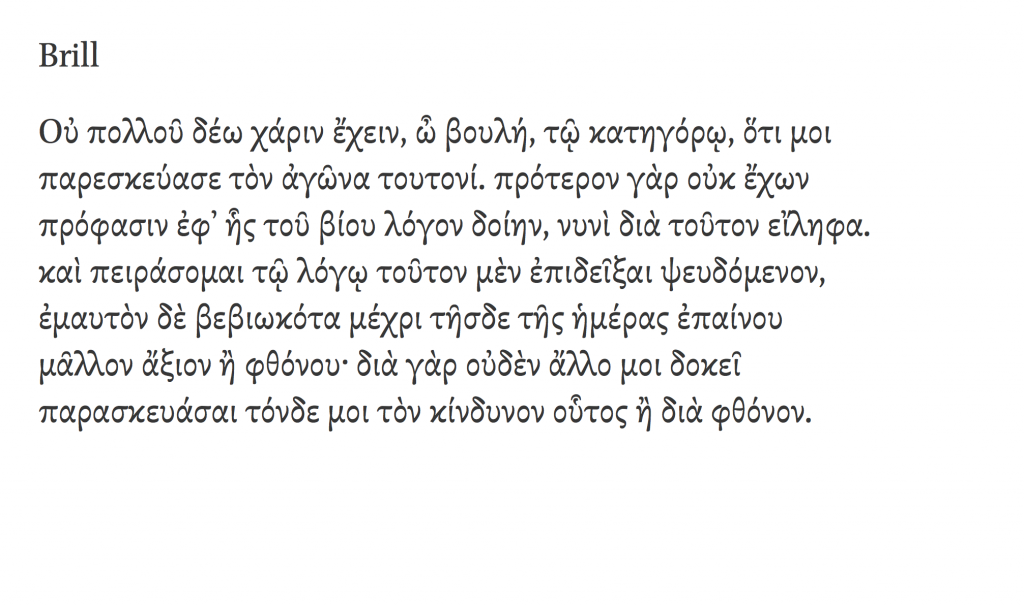

8 Brill (2011)

Μια γραμματοσειρά που σχεδιάστηκε για να αντικαταστήσει το πλήθος των γραμματοσειρών που χρησιμοποιούσε ο εκδοτικός οίκος Brill, που ειδικεύεται στις ακαδημαϊκές εκδόσεις. Για το ελληνικό τμήμα ο John Hudson προσάρμοσε τα καθιερωμένα πρότυπα στις ειδικές ανάγκες του οίκου. Ο Brill ακολούθησε το παράδειγμα της Gentium, και διαθέτει τη γραμματοσειρά ελεύθερα με σκοπό να υποστηρίξει τους συγγραφείς και επιμελητές. Διατίθεται ελεύθερα από αυτή τη σελίδα.

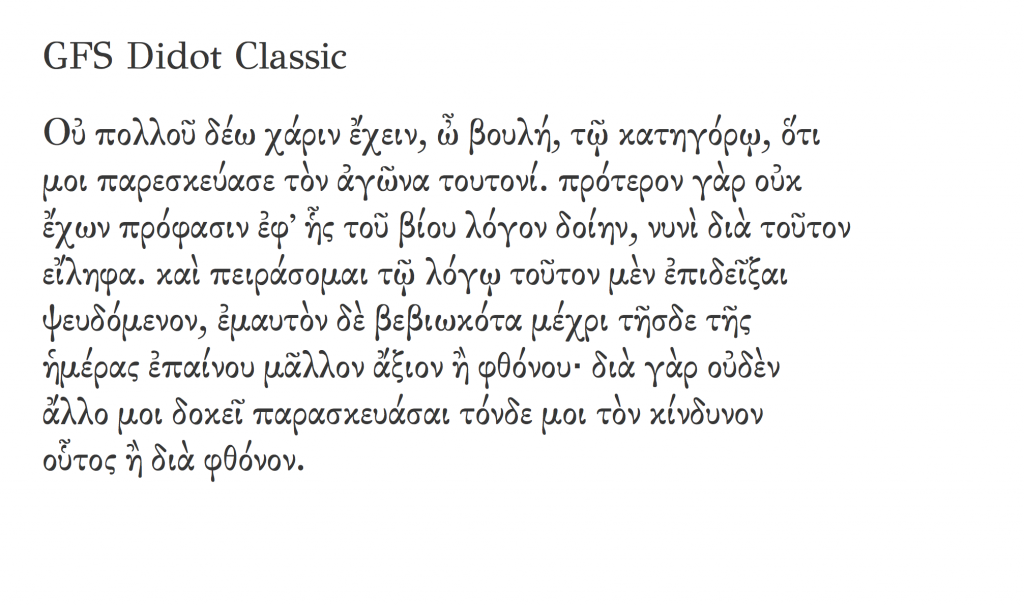

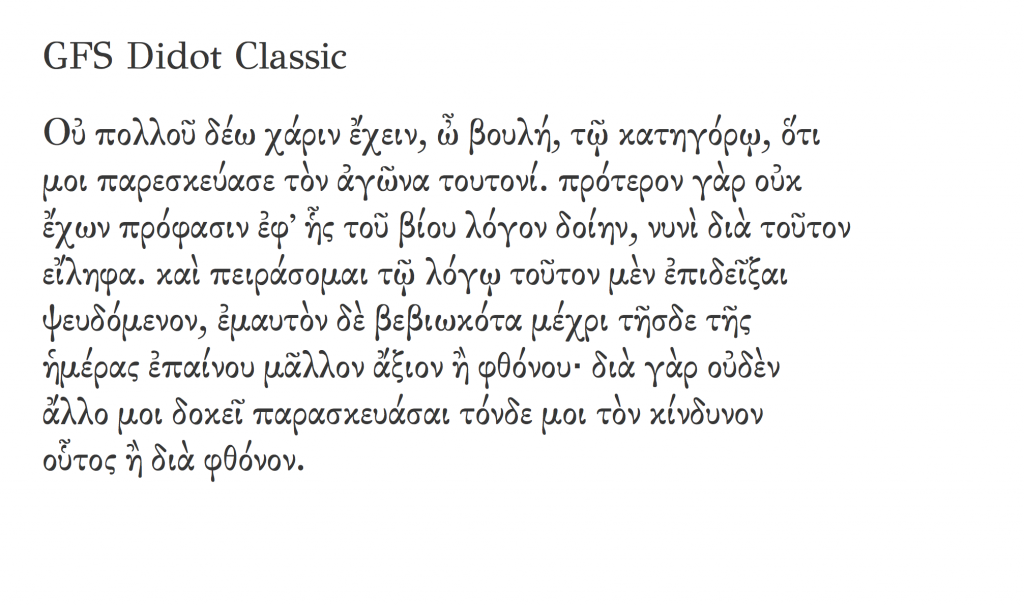

[Συν μία] GFS Didot (2007)

Όπως σημείωσα πιο πάνω, σε όλες αυτές έχω συνεισφέρει, αλλού περισσότερο, κι αλλού λιγότερο. Δε μπορούμε όμως να μιλάμε για πολυτονικές ελληνικές γραμματοσειρές χωρίς να αναφέρουμε τη συνεισφορά της Ελληνικής Εταιρείας Τυπογραφικών Στοιχείων, με κύριο συντελεστή το Γιώργο Ματθιόπουλο. Οι γραμματοσειρές της ΕΕΤΣ βασίζονται σε ιστορικά πρότυπα, και προσφέρονται όλες ελεύθερα. Από αυτές ξεχωρίζω την Didot, που υπάρχει σε δύο εκδόσεις (με λατινικά, ή με εκτεταμένα πολυτονικά).

Υ.Γ. Με σοφή προτροπή του φίλου zvr προσθέτω μια διευκρίνηση: όλες αυτές οι γραμματοσειρές συνοδεύονται από EULA, δηλαδή συμφωνία παραχώρησης δικαιωμάτων χρήσης. Άλλες επιτρέπουν να τις αλλάξεις, άλλες όχι. Άλλες επιτρέπουν μόνο μη-κερδοσκοπική χρήση (π.χ. η Brill) και άλλες μόνο όταν έχεις το λογισμικό της εταιρείας. You get the picture, διαβάστε την άδεια χρήσης. Το βασικό σημείο είναι ότι, από τη στιγμή που ήταν ρεαλιστικό, η υποστήριξη πολυτονικών επιτεύχθηκε και μάλιστα με τρόπο που να επιτρέπει σε χρήστες να γράψουν, να διαβάσουν, και να διακινήσουν πολυτονικά Ελληνικά.

Θα ήταν ωραίο το Υπουργείο Πολιτισμού / Παιδείας / οποιοδήποτε τέλος πάντων, κάποια στιγμή στα πρώτα χρόνια της περασμένης δεκαετίας (ή και νωρίτερα — άνθρωποι σαν τον zvr μιλούσαν για την υποστήριξη ελληνικών απο το 94–95 ήδη) να είχε επιδοτήσει κάτι σαν κι αυτό που έκανε η SIL με τη Gentium, ή η SBL με τη δική της. Και βέβαια αυτοί οι οργανισμοί έχουν τα συμφέροντα και τις σκοπιμότητές τους, αλλά και το όποιο Υπουργείο έχει στόχο την υποστήριξη, ενίσχυση, και εξάπλωση της γλώσσας. Το ότι οι όποιες προσπάθειες δεν έδωσαν μια ελληνική γραμματοσειρά αναφοράς σε διεθνές επίπεδο είναι λυπηρό. (Είναι μεγάλο ζήτημα αυτό το «γραμματοσειρά αναφοράς», και χρειάζεται ολόκληρη ανάρτηση από μόνο του. Ενδεικτικά να πώ ότι μόνο η κωδικοποίηση της αυτόματης αλλαγής από πεζά σε κεφαλαία στις γραμματοσειρές της Adobe πήρε μήνες δοκιμών – και ακόμα δε δουλεύει παντού σωστά, για λόγους που δεν έχουν θέση εδώ).