I measure the growth of my field by the questions of border control agents. A decade ago, the phrase ‘I am a typographer’ would trigger a subtle move of the hand towards the ‘dodgy traveller’ button (just in case, you understand), only to relax once my being in the mapping business was confirmed. But in the last few years – three or four, no more – things are different. I may even drop the words ‘typeface design’, without fear of meeting the agent’s supervisor. And, in some cases, I will be offered the name of the agent’s favourite font, and told about a book called Just my type.

This phenomenon, of typefaces becoming part of the mainstream, is not accidental, nor a fashionable blip. It was foreseeable many years ago, and has been accelerating under the dual impetus of the move to a standards-compliant, text-orientated internet, and the growth of mobile devices with usable browsers.

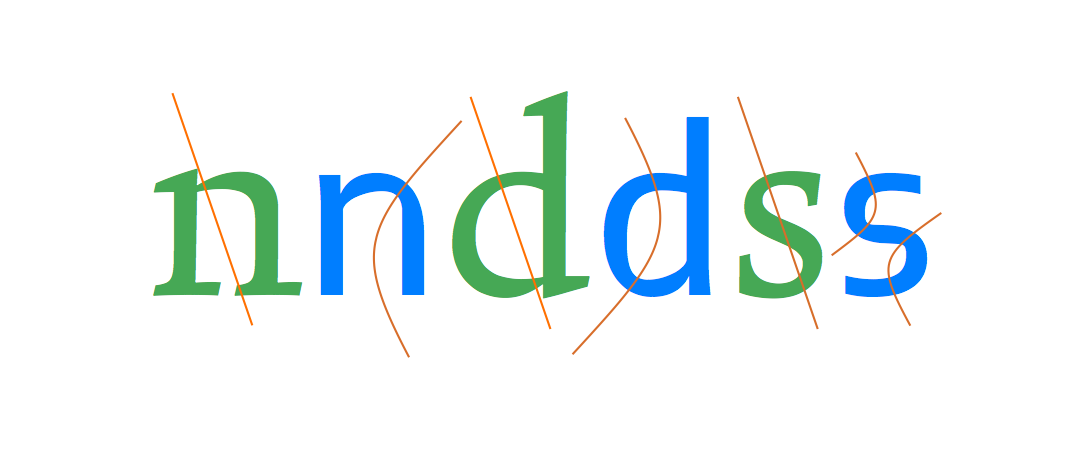

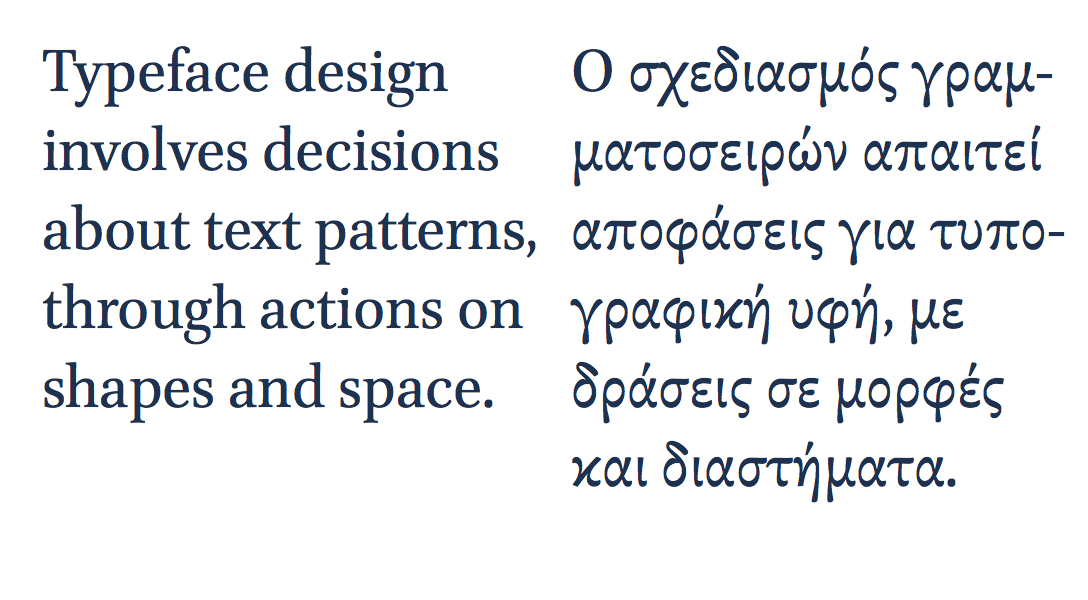

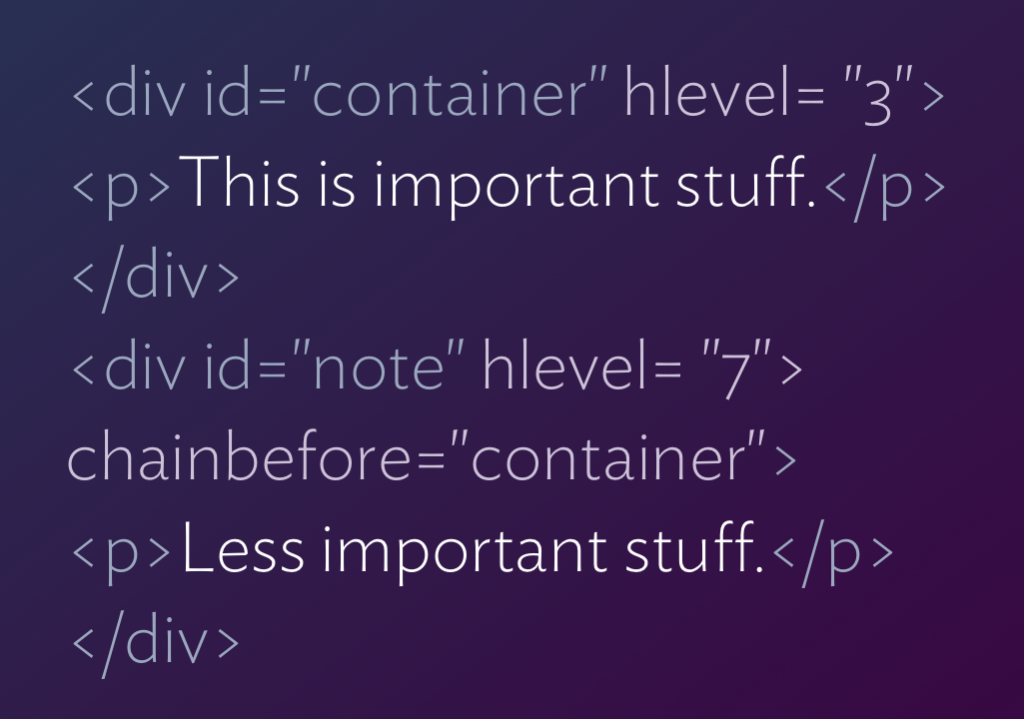

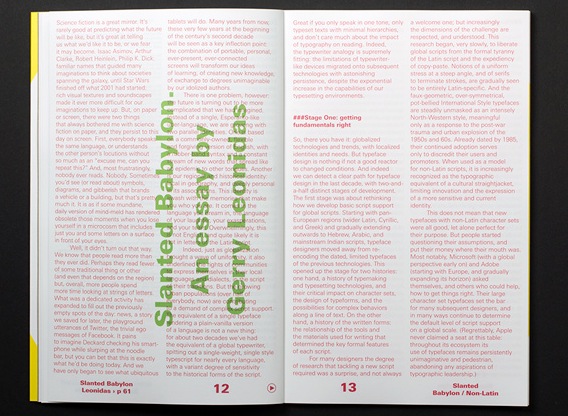

Designers who remember the last decade of the previous century will recall the shift from intensely localised markets with only superficial communication, towards connected regions. The European integration project, from 1992 onwards, followed by the surfacing of the internet onto the mainstream three years later, required fonts that could support a growing number of languages (albeit primarily those written left-to-right, with unconnected letterforms). Fast-forward a decade, and the typefaces on pretty much any up-to-date computing device could render most scripts in the world, even if the more complex writing systems still suffer in fidelity and design range. The two technologies responsible for uniting the world typographically, Unicode and OpenType, are now in a stage of maturity and refinement, covering most of the needs of most readers. (In case you haven’t heard the two names before: Unicode attempts to describe every distinct character used in all written communication; and OpenType allows each character to take the appropriate visual form, depending on context and style.)

Take the core typefaces shipping with an operating system, or a smartphone, or Adobe’s applications: most have well over 2,000 glyphs in each font, with many additional glyphs for stylistic sets like small caps and non-lining numerals, across the Cyrillic, Greek, and extended Latin scripts. Other typefaces cover Arabic, Armenian, Ethiopic, Hebrew, a whole range of scripts for India, and a growing number of scripts for East Asia: from CJK (Chinese, Japanese, and Korean) to Thai, Khmer, and Burmese. All these resources establish a base level for servicing most texts: ‘we’ve probably got some typeface that will render your language, and if you’re lucky there may be more than one, in different styles’. But there are compromises: even if there’s more than one typeface, styles may not match across scripts, and the range of type families is generally uncoordinated. The profusion of styles, widths, and weights of the Latin script is only partly met in other European ones, and far less so in global scripts.

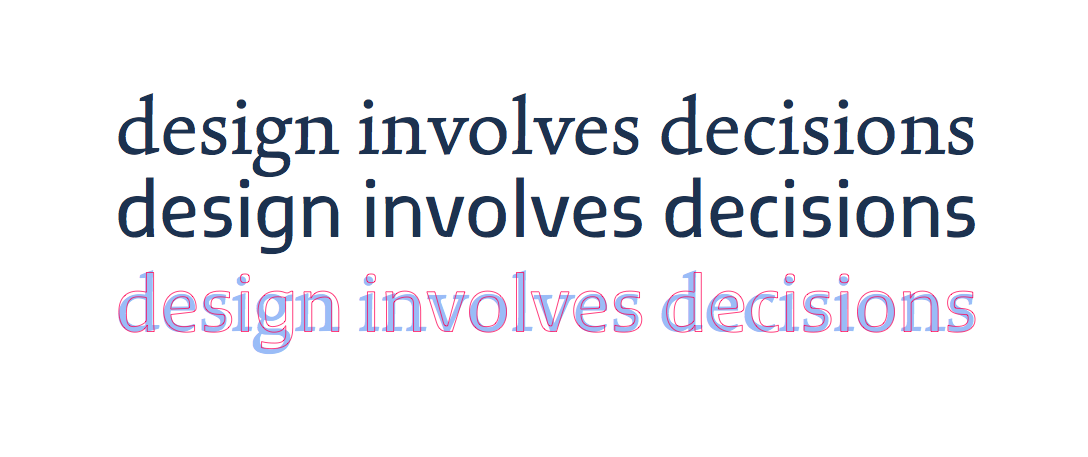

This state ensures basic communication, but is not very helpful for graphic designers and typographers working with global brands, multi-script documents, or with complex applications exclusively in non-Latin scripts. Professionals need a wide range of typeface styles to express the identity of a publication or a brand, and they need the right style in different weights, and widths, and so on. And this is why typeface design is growing, with no sign of abating: a triple combination of growing global brands, a migration to screens of documents with long print traditions (from ebooks and interactive school textbooks on tablets, to local news services replacing traditional newspapers), and a growth of personalised, transactional documents like online shopping catalogues, increasingly on mobile browsers. At the same time, niche print publications are growing: they take up the slack of offset press capacity, but they also thrive in the print runs of a few hundred, a traditional no-man’s land that digital presses have opened up. These conditions, of transformed documents and new platforms, push the demand for ever more typefaces that are typographically rich, wide in script coverage, and tailored for use on a wide range of surfaces: screens, print-on-demand, and traditional presses.

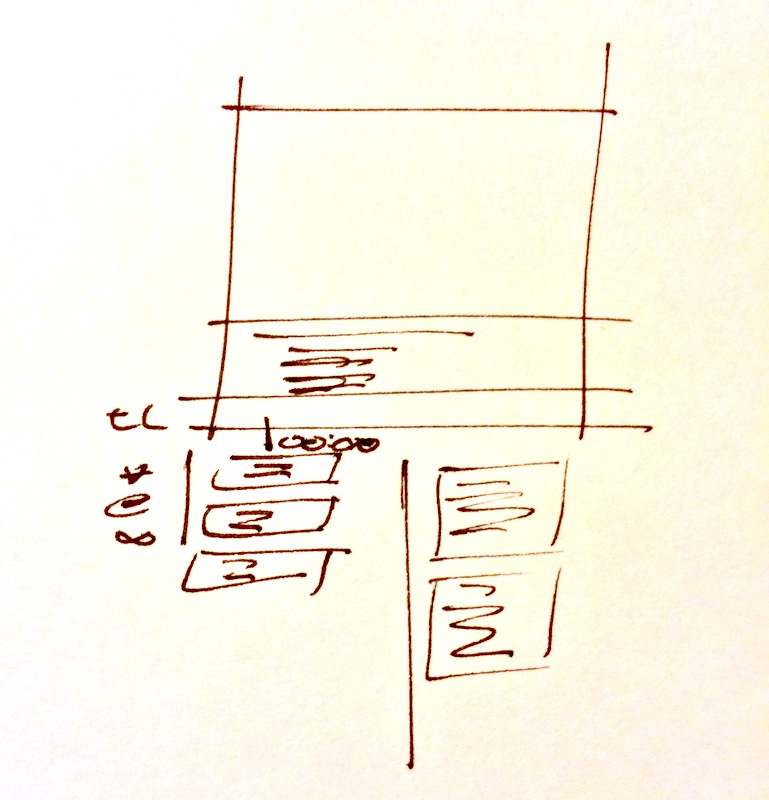

Two factors add substantially to this need. Firstly, the explosion of mobile networks in regions where cable-based broadband is scarce, means that critical communications are restricted to small screens, that render almost exclusively text. Secondly, the speedy adoption of tablets, which are agnostic devices that do not anticipate functional aspects of the documents they render (in other words: the devices do not explain the interaction, like a print document does: the navigation arises from the document’s typographic design, not its ‘hardware’). The four main tools in typographic design become the main carriers of any identity: from a simple publication to a large brand, typefaces, spacing, visual hierarchies, and colour are the only reliable identifiers.

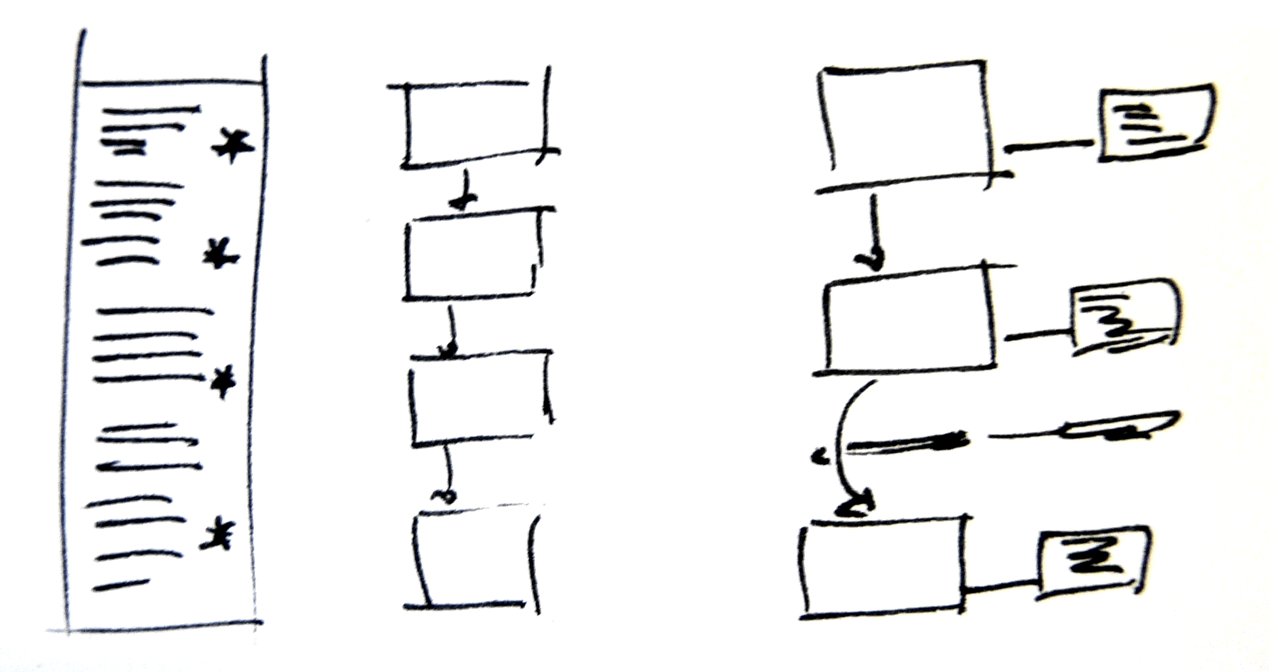

This process has precipitated a radical re-thinking of a typeface designer’s skillset, especially with respect to scripts the designer is unfamiliar with, and most probably cannot read fluently. In such cases, designers need to engage with the characteristics of the script, bringing to the table an understanding of how letterforms are influenced by changes in type-making and typesetting technologies. But just looking at a bunch of local documents is not enough. Designers need to bring an appreciation of the typographic conventions for the genre of documents in each culture. In response to these demands, the best typeface designers integrate research in historical and contemporary artefacts: books and ephemera, type-making and typesetting equipment, but also texts and material such as drawings produced during the type-making process. These combine with a study of texts written by type makers about type-making, designers about their practice, and a range of research texts on the development of typeface design. The key for all these to be included in a commercial schedule is a framework for integrating research into design practice that enriches the designer’s understanding, and unlocks informed creativity.

The weight of methodology and research place multi-script typeface design at odds with art school traditions of design education. There is, quite simply, too much to learn in areas touching on history, linguistics, and technology for self-taught professionals, or the informal osmosis of apprenticeship-based courses. And, rather than be seen as an oddity in the design world, typeface design is in some ways leading a gradual shift in the wider design education sector. Notions of clarifying a body of field-specific knowledge, and formulating a methodology for practice that is transferable across schools and regions are taking off, globally. (Increasingly, I am invited to speak on exactly that subject: how to develop a research-informed, culturally sensitive methodology for teaching that educates potentially excellent professionals. And promotion criteria for design educators worldwide are changing to include research-based outputs, moving design closer to the Humanities than the Arts.)

The growth in books and print magazines dedicated to typography, as well as special sections in broader titles (like the one you are reading now) are just one of the signs of typography maturing. The many conferences, workshops, and exhibitions are another – and they are aimed not only at typographers, but at web designers, brand designers, and graphic designers alike. But there is another, more subtle indicator that typography and typeface design are gradually emerging onto the wider consciousness. As typeface families grow to cover multiple scripts, concepts of national and regional typographic identity become current, and often volatile. New typefaces can reflect both home-grown and imported visual trends; they give concrete form to the expression of community identities, and become inflection points in visual culture at a range of levels. Beyond functional requirements, they can embody political and generational shifts, and encapsulate a society’s dialogue with modernity.

Next time I cross a border, I’ll have a longer tale to tell.

[Published originally in In Computer Arts Collection: Typography Vol 2 no 2, 2013 and republished, slightly edited, on this site as The next ten years.]