The text below is a pre-publication version of an article that appeared in Information Design Journal, in 2000. Although somewhat dated, it is useful for typeface design students. It picks up references from a cluster of texts from four issues of Visible Language that form part of the sources for one of the seminars in the MATD and MA (Res) TD:

Donald E Knuth, ‘The concept of a Meta-Font.’ In vol XVI, no 1, 1982

Douglas R Hofstadter, ‘Metafont, metamathematics, and metaphysics.’ And:

[various] ‘Other replies to Donald E Knuth’s article, “The concept of a MetaFont”.’ In vol XVI, no 4, 1982

Sampson, Geoffrey, ‘Is Roman type an open-ended system? A response to Douglas Hofstadter.’ And:

Douglas R Hofstadter, ‘A reply from Douglas Hostadter.’ In vol XVII, no 4, 1983

Donald E Knuth, ‘Lessons learned from Metafont.’ In vol XIX, no 1, 1985

**********************

No review of digital typography is complete without a long stopover in Don Knuth’s neighbourhood. A mathematician based in Stanford, California, Knuth is primarily active in the field of computer programming. During the mid-1970s, out of frustration with the quality of phototypeset mathematics, Knuth was driven to address the problem of at least matching the standard of hot-metal Monotype output. [1. Knuth’s first two volumes of The art of computer programming (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1968 and 1969 respectively) were typeset on Monotype machines. A good source on the standard achievable by hot-metal composition is the winter 1956 issue of the Monotype Recorder (vol. 40, no. 4), which was devoted to the setting of mathematics with the Monotype 4-line system.] The product of this endeavour was Tex, a versatile and powerful typesetting system which outputs device-independent documents. Alongside Tex, Knuth developed Metafont, [2. Knuth typesets Tex and Metafont as TEX and METAFONT respectively through-out the book. Here the words are treated as software titles, not logotypes.] a system for generating typeforms. (The term “typeform” is used to signify the rendering of a typographic character, therefore a mark intended to function in conjunction with other marks with which it forms a collection (normally a typeface), without prior knowledge of the context of its use. On the other hand, a letterform is a one-off mark produced for a particular context, e.g. a manuscript or a piece of calligraphy.) From early on Knuth made both systems freely available, and it is not an overstatement to say that Tex has transformed the production of scientific writing. Tex users number in the tens (if not the hundreds) of thousands, and it will be a rare math-intensive paper that is not so typeset.

Digital typography, published in 1999, is the third in a planned series of eight books of Knuth’s published works, together with some new material. It is a hefty 680 pages, comprising 34 papers and articles, including the transcripts from three relatively recent question & answer sessions. The majority of the contents has been previously published in TUGboat, the journal of the Tex Users Group. Knuth has already begun the process of identifying errata; characteristically, readers who contribute can look forward to a reward of $2.56. (The list is updated at Knuth’s Stanford page.) To his credit, not only is the prose very readable, but the mathematical exposition managed to flatter this reader that half-forgotten business studies algebra was up to the task of digesting the arguments. However, for reviews on the programming content, and opinions on literate programming (an area of Knuth’s activity to which he attaches great importance), readers are advised to turn to TUGboat vol 20, No 2, 1999: its editor has announced reviews by Knuth’s fellow computer scientists.

At one level, the book is an archival collation of technical papers and notes; at another, it is a source of pertinent ideas and fascinating suggestions – especially so when addressing the nature of letters and typeforms. Inevitably, the more technical chapters will make non-specialists feel they are eavesdropping on a conversation having missed the key remark. Even so, reading the early projections back-to-back with the mature re-evaluations (mostly through the question & answer transcripts) sheds a revealing light on the development of a significant body of work.

The papers fall in two broad categories, Tex and Metafont, with a few further items on rasterization. Of the two main themes, Tex is the more significant, if less interesting – a corollary of its undisputed status: the value of Knuth’s contribution to electronic typesetting is as significant as the superiority of Tex’s line-breaking algorithms over pretty much anything else available now, let alone twenty years ago. Indeed, it is only this year, with the launch of Adobe’s InDesign that we get a ‘multi-line composer’ – a line-breaking algorithm that monitors several lines before fixing line-breaks. Adobe properly acknowledge the credit, [3. See ‘Adobe InDesign in depth: text and typography’ pp. 3–4, 8.6.99. Adobe’s description of InDesign’s ‘multi-line composer’ is impressively close to Tex, and they even use the term ‘badness’ (a Tex trademark) in their documentation.] but, at the time of writing, it remains to be seen whether InDesign can match the typographic texture Tex can achieve.

Tex is based on the twin concept of approaching documents as lists of boxes joined by stretchable ‘glue’, and defining values of ‘badness’ for deviations from optimal spacing values. Knuth repeatedly mentions that the potential of these simple premises was not fully foreseen. Indeed, a non-Texpert looking at the typesetting complexity of material produced with Tex cannot but admire the elegance and economy of the concept. In this respect Digital Typography is a showcase item – and if the typesetting of the mathematical matter is more obviously impressive, the evenness of the texture in less extravagant pages sets a subtle benchmark. (The only gripe in this department being a propensity for too-wide, almost double, spaces after full stops – an annoyingly persistent legacy of typists, which is avoidable in Tex.) Indeed, the combination of quality printing on good paper and the effectiveness of Tex is enough to render the singularly unattractive Computer Modern typeface used for most of the book digestible, by any standards no mean feat.

By far the more interesting parts of the book are the chapters on the inception, development, and use of Metafont. Particularly enjoyable for documenting the evolution of a design is the chapter on AMS Euler, a typeface family for mathematical typesetting that Knuth developed in association with Hermann Zapf for the American Mathematical Society. [4. One cannot help but think that Zapf, probably the best known representative of the calligrapher-as-type-designer approach, was the ideal choice for a meta-collaborator: Zapf’s technique lends itself readily to interpretation in the Meta-font idiom. It is tempting to speculate on developments had Knuth collaborated so closely with a type designer from a punchcutting or drafting background. It is, however, interesting to compare other documented uses of Metafont for large projects (see, for example: Southall, Richard, ‘Metafont in the Rockies: the Colorado typemaking project.’ In Roger D. Hersch et al (eds.), Electronic publishing, artistic imaging and digital typography. Berlin: Springer Verlag, 1998, pp. 167–180, where the emphasis was on control of the rasterized output).] Predictably, work on Metafont started as an attempt to address the practical problem of supplying typefaces for Tex – remember, this is long before the days of PostScript and TrueType, and digital typefaces suitable for mathematical typesetting were thin on the ground. Knuth’s original goal was ‘to find a purely mathematical way to define the letter shapes and to construct the corresponding raster patterns’. [5. Digital typography, p. 35] This statement can be something of a Pandora’s box, depending on whether one interprets ‘to define letter shapes’ to mean: ‘to codify an explicit description of a typeform (or a group of typeforms)’ – or: ‘to specify a process for the generation of new typeforms’. Throughout the book, one gets the impression that Metafont does the one thing, and its creator thinks (sometimes, at least) that it can do the latter, as if Knuth saw in Metafont more than the technology implied. In Digital Typography he recounts how he studied letterforms and saw regularities in the design, from which he realised that he ‘shouldn’t just try to copy the letterforms, but [he] should somehow try to capture the intelligence, the logic behind those letterforms’. [6. Digital typography, p. 607] One cannot but think that, at some point, Knuth must have made a mental leap from devising a description system for typeface families to a broader generic system for typeform description and generation. Perhaps it was his enthusiasm for letterforms that led him to such statements. In any case, this quote raises two fundamental questions: given that there is some ‘intelligence’ behind typeforms, is it possible to make it explicit? And, secondly, assuming that it is so, is it possible to codify this ‘intelligence’ in mathematical terms?

In any case, Knuth seems to have been aiming at a new approach for designing a typeface family, an approach that could ensure consistency in the design of various, not necessarily predetermined, weights and styles. (A goal that Adobe’s Multiple Master fonts have also sought to address – bar the ‘not necessarily predetermined’ bit.) The first version of the system, Metafont 79, defined ‘pens’ and ‘erasers’, and prescribed the trajectories between co-ordinates in two dimensions that these pens (or erasers) would have to execute in order to render each typeform. The dimensions and behaviours of pens and points were parameters definable by the user. A particular Metafont would be a collection of a finite set of parametric mark-makers and behaviours, each parameter assuming one of a potential infinity of values. In other words, using a single ‘master description’ infinite variations on a theme could be output. Key to this point is the fact that there exists not a singular, explicit collection of typeforms from which variations are extrapolated; rather, the specified parameters define a ‘design space’ within which any instance is equally valid as the next one. In essence Metafont-the-application is a system for the description of categories of typeforms; each Metafont-family is a classification system with a fixed number of ‘pigeonholes’ of infinite depth; each Metafont-typeface the compilation of a selection from each pigeonhole.

Knuth’s scientism was presented as the most recent chapter in the book that started with Felice Feliciano in the 1460s, continued with Damiano da Moyle, Fra Luca de Pacioli, and nearly twenty others, to reach a spectacular highpoint around 1700 in the engravings supervised by Phillipe Grandjean. Almost with no exception, these attempts at instructing on the ‘correct’ or ‘proper’ formation of letterforms (mainly capitals) were no more than fascinating red herrings of rationalisation. The most important exception to this trend was the Milanese scribe Giovanni Francesco Cresci, who pointed out the futility of his contemporaries’ propositions – and is in fact quoted in Digital Typography. But Knuth then does an about-face and writes: ‘Well, Cresci was right. But fortunately there have been a few advances in mathematics during the last 400 years, and we now have some other tricks up our sleeves beyond straight lines and circles. In fact, it is now possible to prescribe formulas that match the nuances of the best type designers’. [7. Digital typography, pp. 38–39] This remark can be interpreted as either ‘we can codify an existing design without any information loss’ (which is perfectly acceptable), or ‘it is possible to specify algorithms for the creation of letterforms’ – we should add the caveat: to Cresci’s standard. Neither of these interpretations is a correct description of Metafont, but the latter is closer to Knuth’s writing about it.

Metafont is a tool for creating typeforms in the same way that a chisel is for creating letterforms. A meta-designer will approach the computer with more or less pre-formed intentions about the general style of typeforms, if not a wholly clear notion of a specific instance of the Metafont he will be defining. He would then have to mentally translate his intentions into the Metafont grammar of pens, erasers, trajectories, and edges, and enter the appropriate code. And, as with all similar activities, we can expect the designer to undertake several proof-and-revision cycles until the result is deemed satisfactory. The meta-designer uses a computer to facilitate the expression in a usable format of a pre-conceived set of typeforms, in the same way as someone using Fontographer or FontLab: the concept of a typeform is visualised internally, then translated into a formal grammar understood by a tool, then entered in the tool’s memory for processing. For sure, as with all tools, Metafont will in some way affect this ‘double translation’ of the designer’s intentions. But to claim that Metafont aims in ‘the explicit implementation of the design ideas in a computer system’ [8. Bigelow, Charles, [contribution to] ‘Other replies to Donald E. Knuth’s article, “The concept of a Meta-Font”.’ In Visible Language, vol. XVI, no. 4, 1982, p. 342] misses the point that Metafont simply implements the product of the design ideas in a specific medium. What results from meta-designing is nothing more than the final trace of the process, not in any way a representation of the design process itself – let alone the ideas that generated it. Ultimately Metafont rests on two flawed assumptions: one, that by studying the finished product of designers’ work we could understand what was going through their minds, and isolate these intentions from the effects of their tools; and, two, that we could then express the range of these intentions in code for a computer ‘to carry out the same ideas. Instead of merely copying the form of the letters, […] to copy the intelligence underlying the form’. [9. Digital typography, p. 8]

What is important in type design? Type designers would say: patterns, relationships, the interplay of negative space and positive mass. A designer may intellectualise the design process ex post facto, but it is highly questionable that this process can be made explicit before the design is complete – indeed, it is safe to assume that it is largely crystallised during designing. To seek to represent the internal process of designing as the making of marks is to mistake a procedure for its motive.

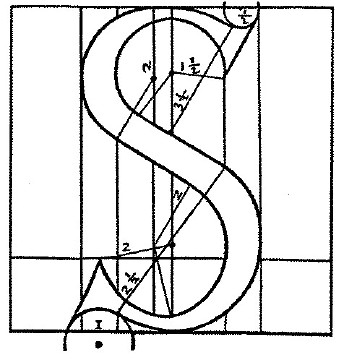

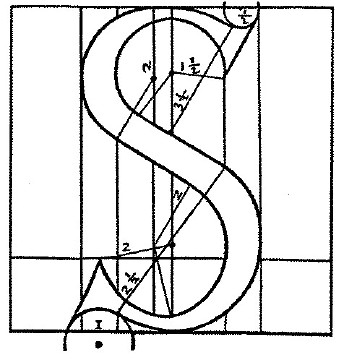

Given that a considerable part of Knuth’s research was based on manuscript books and fine printing (that would, most probably, make use of oldstyle typefaces), it was perhaps not unexpected for him to adopt a model that replicated the rendering of calligraphic letterforms. However, the fluidity and potential for optical balance in formal calligraphy does not survive in Metafont. It is indicative that, in the process of refining the mathematical description of an ‘S’, Knuth chose Francesco Tornielo’s geometric description from 1517. Tornielo’s essay was one more entry to the list of the Renaissance geometric fallacies that started with Feliciano – one could add that Tornielo’s were among the less beautiful letterforms. Knuth follows and amplifies Torniello’s instructions, then ‘solves’ the problem of a mathematically correct representation of the ‘S’. However, even though the meta-S is far more detailed and flexible than Tornielo’s, it does not hold any information on what makes a good ‘S’.

It could be argued that a procedural model that replicates an existing, non-computer-based activity does little justice to the potential of computers as design tools. A computer application for designing typeforms is unconstrained by lettering procedures. Shouldn’t this liberation suggest a new design paradigm? In its ductal rationale Metafont is suggestive of a digital version of Gerrit Noordzij’s scheme for description and classification of typeforms according to the translation and expansion of a rendering nib. [10. Noordzij, Gerrit, The stroke of the pen: fundamental aspects of western writing. The Hague, 1982. (A somewhat expanded version of this paper was published under the title ‘Typeface classification’ in the first volume of Bernd Holthusen & Albert-Jan Pool, Scangraphic digital type collection (edition 4). Mannesmann Scangraphic, 1990, pp 65–81)] But Noordzij has his feet firmly planted in the western lettering tradition, and approaches typeforms as inextricably linked to this background. Significantly, his analysis is exegetical, and not intended as a tool for the generation or manipulation of new typefaces. Furthermore, Noordzij acknowledges the presence of exceptions outside the possible design space (the ‘typographic universe’) of his system. This internal consistency is not obvious in Metafont’s approach, in which analysis of one idiom is presented as a tool for describing typeforms of any pedigree. In other words, Knuth adopted an idiom that seems foreign to his tools. Admittedly, the significantly redesigned Metafont 84 made provision for the definition of typeform edges, but Knuth still believed that the pen metaphor ‘gives the correct “first order” insights about how letters are drawn; the edge details are important second-order corrections that refine the designs, but they should not distract us from the chief characteristics of the forms’. [11. Digital typography p. 330]

For a type designer from a non-calligraphic background the ‘moving pen’ paradigm will probably limit the formal freedom of defining typeforms on a virtual plane. The designer will have to translate the contours and patterns in his mind to the grammar of Metafont, a process which is counter-intuitive – not to mention the possibility of the intended forms being unreasonably difficult to convert into Metafont. Moreover, type designers do not generally think in nebulous trends (‘some sort of serif about here’ or ‘a bit of a notch around there’) – they tend to approach new designs with a set of curves or patterns, in positive or negative space, that they then develop to construct the whole of the typeface. In this respect the flexibility afforded by Metafont in creating new designs is of debatable benefit.

This issue highlights a common denominator in discussions of digital type: the relationship between the designer’s intentions and the typeforms that are finally rendered is not fixed. The designer will record disembodied – perhaps idealised? – typeforms as they would render under hypothetical, ‘perfect’ conditions, then edit the font data or enrich it with information to make the typeforms render as faithfully to the original intention as the technology allows. It is arguable that, to some extent, a similar process existed in all typeform-making technologies. However, currently available type design software depends heavily on this dissociation of intended and realised typeform. PostScript Type 1 fonts are the best example of this: dependence on a system- or printer-resident rasterizer for rendering means that as the rasterizer is upgraded the same font information may generate different output. In TrueType fonts rasterizing is primarily controlled by information in the font file itself, but the process of specifying this information is quite distinct from the design of the outlines. Metafont is exceptional in that the typeforms generated from the user’s definitions of [groups of] typeforms are inextricably linked to the resolution of the output device. ‘Pens’ are digitised to the appropriate raster before rendering the typeforms. It is also possible for the user to define explicitly the raster frequency, as pixels-per-point or per-millimetre. In other words, the ‘enrichment’ is not a separate stage in font design and production, but an integral aspect of working with Metafont. It might well be that in this respect Metafont’s approach is truer to the digital world – or not?

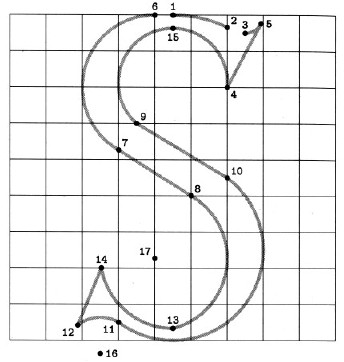

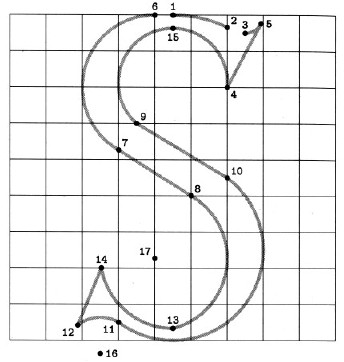

{{work:4_dekmetafonts.jpg|The middle S in the sequence of the previous illustration with defining points highlighted. Notice the white regions in the counters, where “erasing” has been specified}}

There is another argument against Knuth’s scientism: Metafont fails the typographic equivalent of the Turing Test. He asserts that ‘Metafont programs can be used to communicate knowledge about type design, just as recipes convey the expertise of a chef’. I would argue that neither is the case, but I am not a professional cook. To stick to the culinary analogy, however, Metafont can be seen as one of those multi-function tools that chop, grate, slice, and generally do faster and in some cases better all sorts of things that you could do by hand – but it does not join you at the table when the dinner is ready. Can we supply a computer-literate person with the Metafont-programs for a typeface family, and in any way expect them to develop an understanding of the original designer’s concepts for the design?

Indeed it was a designer and educator with far more experience than this writer that interpreted Metafont as implying that ‘the parameters of a design are more important than the design itself – that is: than the idea behind the design and how the face looks and reads’. Here our attention is pointed to a fact that Knuth seems to overlook: typeforms are social animals. Type designers must marry their personal (culturally coloured) viewpoint with their speculations on the reception of their typeforms within their environment. Furthermore, it does not follow that the eventual interpretation of the typeforms will be the anticipated one. This cycle inevitably informs the design process. The changing appreciation of designs through time is witness to how the same typeform – the same procedure – can elicit different interpretations. (Does Akzidenz Grotesk carry the same connotations today as it did at the turn of the century?) Conversely, if the environment within which a typeform is created is foreign to us, Metafont’s ‘capture of the intelligence behind the design’ will not reveal the designer’s intentions. (If a contemporary designer works in a script we are not familiar with, could the Metafont files offer insight into which parts of typeforms were essential elements, and which were embellishments?) Since the computer operates in a social vacuum, it cannot understand what it’s doing. Not only is Metafont merely replicating a procedure, but its product is meaningless within the computer’s frame of reference: Metafont cannot judge whether the typeforms it generates are acceptable in the type designer’s environment. In other words, it is possible that an instance of a meta-typeface is valid within the Metafont-system (indeed, assuming a debugged program, it would not be produced were it not so), but not acceptable in the social context.

Now the reasoning behind the caveat about generating letterforms ‘to Cresci’s standard’ becomes obvious: the qualitative sufficiency of the outcome is not guaranteed by the otherwise valid implementation of a Metafont. Knuth has forgotten his brief recognition that Cresci had got it right. Like a true descendant of the 15th century deterministic letterers so enamoured of the ruler and compass, he defines a formula for determining the optimal curvature at a given point along a typeform. But what he comes up with is, inevitably, his own interpretation of a ‘most pleasing curve’. Clearly, each type designer has his own inner set of ‘most pleasing curves’, proportions, and patterns that he returns to in each design. It could probably be argued that the mathematical expression of curves constrains the range of possible ‘most pleasing’ curves for each circumstance. (W. A. Dwiggins might have had something to add to this. While he was satisfied with the Mergenthaler draftsmen’s transfer of his own drawings to blueprints for pattern-making, he did comment on the over-regularised Legibility Group typefaces. In copying Dwiggins’ drawings the draftsmen were only using their french curves to follow patterns that had been designed according to one person’s vision. On the other hand, the Legibility Group typefaces were designed in-house, and – despite C. H. Griffith’s supervision – were a collective effort. It is not difficult to imagine that in such an environment french curves would suggest patterns, instead of just follow them.)

The subjectivity of what constitutes a ‘most pleasing curve’ is borne witness by the variety of opinions on any type design. Despite any generalisations we may care to make, the optical compensation of shapes so that they look and feel correct, rather than actually measure so according to a geometric rule, is very much up to the designer’s judgement (and retina). It is this subjectivity which demands that every type designer goes through long printing out, looking at, editing, and starting-all-over-again sessions. It is the presence of these internal, deeply subjective ‘french curves’ that gives rise to the re-visitation by many designers of similar themes across quite different typefaces. In this respect, by drawing on existing cultural patterns and expanding on them to create new, personal interpretations, is it an exaggeration to compare typeface design to composing a piece of music, a case for type design as jazz?

When Knuth’s concepts first reached a wider, typographically-minded, audience the debate generated arguments that still resonate. At its best, Digital Typography is a source of provocative inspiration, an opportunity for debate that should not be missed. Its challenges should be heartily taken on by typographers, type designers, and educators alike. We may disagree with Knuth’s adherence to Tornielo’s ways, but his thoughts have brought us that little bit closer to our search for a Cresci for the digital age.

‘In search of the digital Cresci: some thoughts on Don Knuth’s Digital Typography‘. Stanford, CA: CSLI Publications, 1999. In Information Design Journal, vol 9, no 2 & 3, 2000, pp 111–118