The re-issued form magazine dedicated an issue to design education. Anja Neidhardt asked me four questions, as part of her research for her article. (The issue can be read on Isuu via the form website.) Here are my answers to Anja’s questions:

At Typo Berlin (if I remember right) you said about teaching: “What we do is: We cheat”. Please explain this statement.

The context for this sentence was a longer statement about the nature of typographic and typeface design. Typography happens in contrast with other areas of design, where the functional conditions are relatively simple and the space for formal experimentation relatively wide. In the typographic disciplines we look to past practice as a guide to the assumptions that users will make in each circumstance. This happens because the design objectives are relatively complex (the information density is high) and their configurations relatively stable (a news article has a similar structure on a print newspaper as on a smartphone); and because the consumption of typographic design is iterative, and cumulative: changes take place in an environment of many similar objects used concurrently, within a continuum of experience by each user. In other words, the more radical a change, the more it needs to echo and relate to pre-existing structures and affordances. The use of visual metaphors in interface design is a typical case of this mechanism.

So, designers rely on a whole range of pre-existing decisions for their own designs to make sense. In the best case, these pre-existing conventions are consciously acknowledged; in these cases the designer can engage in depth with his subject, and improve the discipline. But in many cases designers are only partially aware of the way conventions have been formed, and how their own ideas are influenced by the design environment. In these cases, designers “cheat” in the sense that their work feeds off past projects without due recognition.

How does education in the field of typography look like today? What should be changed, and why?

It is possible to see strong growth in some areas, and early signs of risk in others. My own niche area of typeface design is experiencing strong growth, and will continue to do so for many years, in response to the globalisation of typographically complex documents, and the need to support text-intensive environments. The result is a lot of new courses at a range of levels, and a strong interest by both younger and more experienced designers to study. With regard to document-level typography (from a periodical publication to newspapers to reference works) there is a critical transformation in progress, with inadequate response by education institutions globally.

Until roughly the last decade the design and the production spheres were relatively separate, and with clear professional roles (in other words, a designer was not also the printer). The situation nowadays is different, where the “maker” may be a designer as well, or work in an environment with a lot of overlap (the person who writes the code to render a text on screen may implement a specification by someone else, but may just as easily devise the typographic specification him/herself).

This new environment, where the typographic specification has, in fact, a high overlap with the encoding of the text, places new requirements for typographic education. The easiest examples are those of “conventional” publications like novels and magazines turned into ebooks and tablet-based apps. The old model called for a relatively stable typographic specification, implemented by typesetters and printers who made the content of authors and editors appear in print. In contrast, we now have typographic specifications that are not only fluid across platforms and use scenarios, but also across time: the typographic design changes often in little steps, instead of only every few years in big ways. And, whereas the roles of authors and editors may be clear, the “makers” (designers and coders who make the content appear on each device) are now melded into multi-skilled individuals, or closely integrated teams (at least where things go well).

It is my impression that design education has not responded fast enough to the challenge of these new models of publishing, and have not acknowledged the need to respond to the demand for these new roles. Furthermore, we are now at a stage where “tradition” typographic education is at risk of falling behind. The sequence in which complex documents are migrating to screens, and the way in which content is specified, has helped establish some basic parameters for on-screen typography that makers can refer to while maintaining the readability of documents, but lacking the skills and understanding to deal with more complex information structures (this is a kind of “cheating” like that discussed above).

Colleges and universities teaching typography face the challenge of adapting to a typography that is personal, portable, responsive to its context and that of the reader’s route through texts, that references established conventions, that integrates time-based elements, and even jumps across may possible combinations of all these parameters. The ones that respond to this challenge will have strong growth ahead, but I think that the difficulty of radical change in many institutions puts typographic education at risk.

On the one hand there are many, many fonts made for the latin writing system. But on the other hand there is a lack of fonts in some countries. How can students be taught to design typefaces for languages they don’t speak?

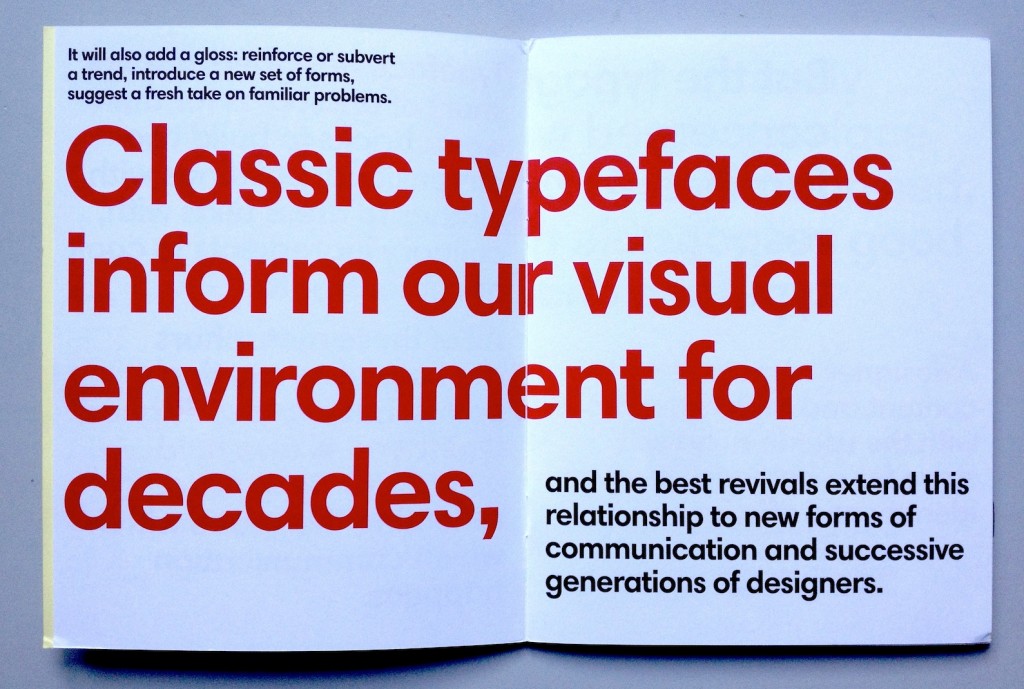

Indeed, in recent years we see an overdue push to cover gaps in global typeface design coverage, both in wide character sets (multi-script typefaces) but also in extended typeface families in non-Latin scripts. This corrective is a response to changes in type-making and typesetting technologies, the growth in the range of documents (in the widest sense of the word) produced in global scripts, and the spread of readership in new demographics. Although digital technology liberated the type-making tools from the geographic restrictions of previous technologies, the know-how and support resources have remained, for many scripts, near the traditional centres of typeface design. It is not surprising, then, that designers who are experienced in some scripts may be called on to design typefaces in new scripts – a practice reinforced by existing professional networks and the focus on business development in English. In practice, professional designers may be expected to build experience in a whole range of related or unrelated scripts. The education challenge is then clear – and pressing, since the market is growing faster than existing designers can develop their skills.

Four areas need to be addressed for a student to develop non-native design skills (and the same for a designer experienced only in their native script):

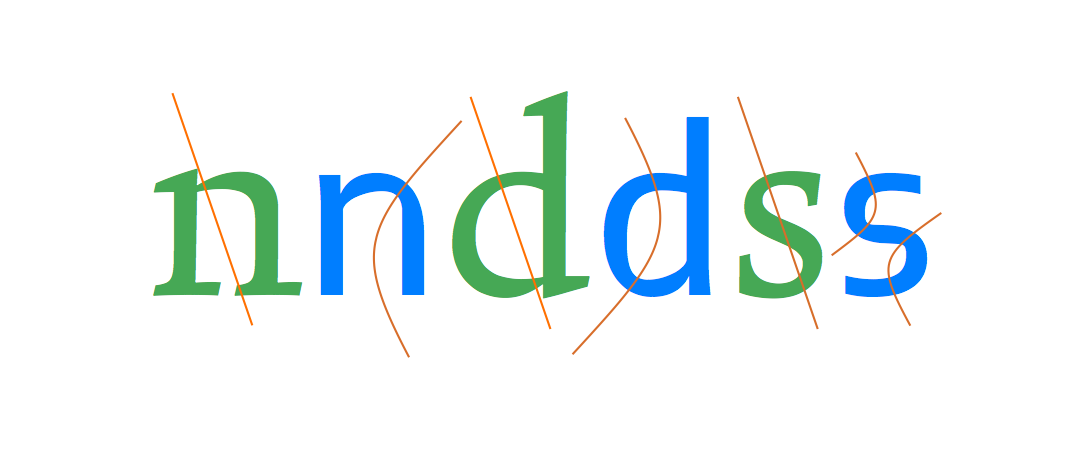

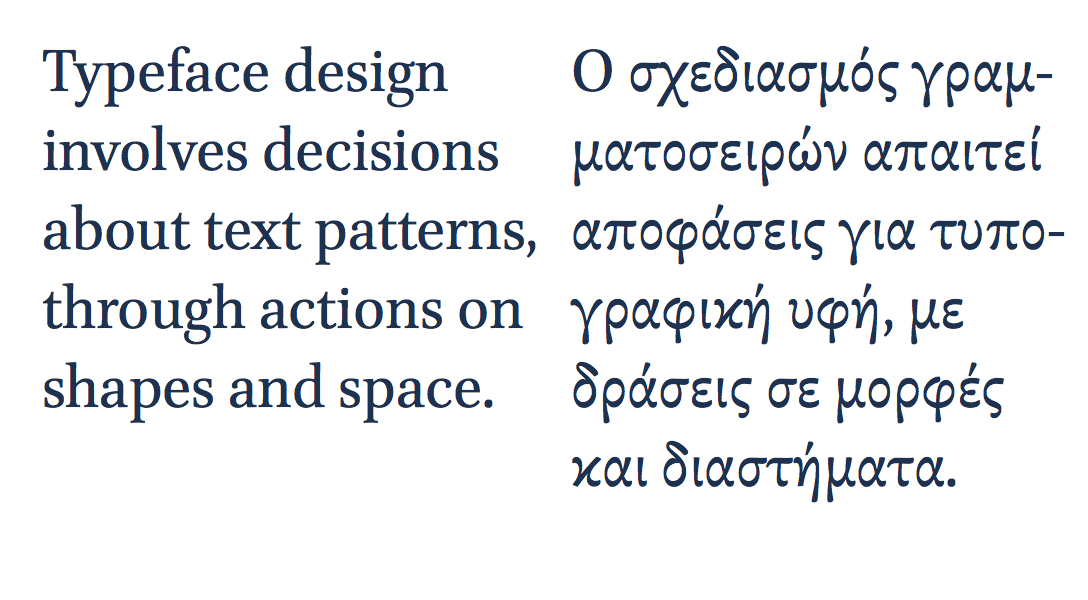

First, and most fundamentally, an understanding of the historical development of the written and typographic script as it currently stands, with particular focus on the impact of type-making and typesetting technologies on the form of individual characters, the character set and any composition rules (esp. substitution and positioning).

Second, an exploration of the key combinations of writing tools and movements that generate “valid” letterforms and words in the script. This is particularly important in all the scripts that have a much closer relationship to written forms than the Latin (which is, in fact, the overwhelming majority).

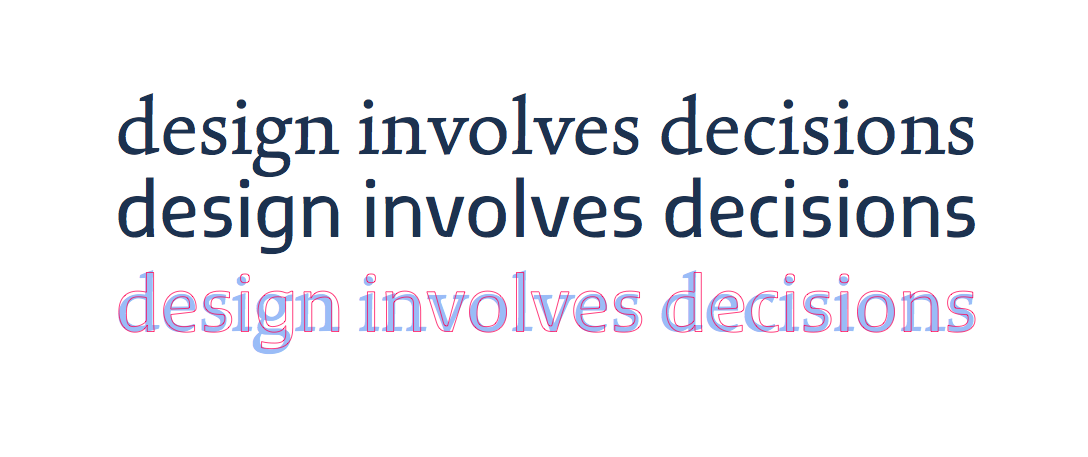

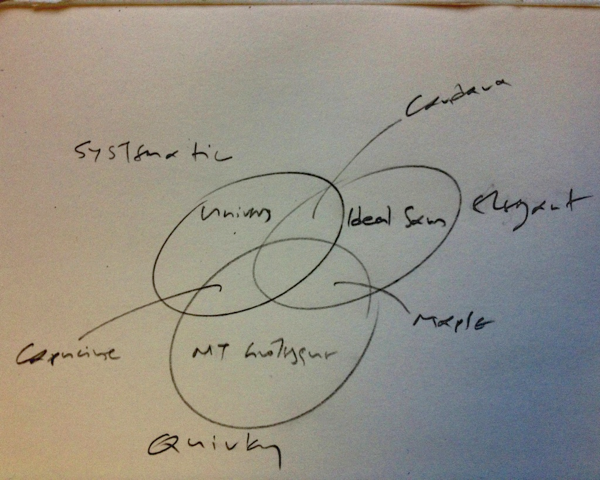

Third, an understanding of how existing styles correspond to specific typographic structures, and how they are used in native documents. (For example, how is hierarchy, emphasis, and differentiation in tone indicated in the typography of the non-native script? What is the practice when equivalents to styles like “italic” or “thin” are not present?)

Fourth, an understanding of the tension between tradition and modernity in the context of the local visual culture. This forms the basis for progressing beyond mere adaptation towards originality and even innovation. The role that lettering can play in inspiring alternate styles is a key example of this area; another is the relationship of stroke properties to established styles (for example, in one script a monoline stroke may be considered “default and traditional” whereas in another the loos of contrast may be a radical proposition).

While developing a critical understanding of the non-native script, students also need to do some text analysis. This will give them insights into the combinations of letters and the patterns of shapes (just as a German designer will also test their Latin typeface with texts from all European languages). Unlike the four areas of learning, this is a process that is easy to share amongst designers, and pool the results, which can then be converted into common test documents.

It is, of course, important to seek feedback from native readers, but not any native reader – even if they are design professionals from the native community. Feedback needs to be sought from people who can give type-specific comments, which are fairly specialised. (Graphic designers, for example, are used to seeing type in a different scale from type designers, and tend not to understand the cumulative effects of detail changes within individual letters.) And before readers instinctively object, it is useful to be reminded that there are many examples of exceptional typefaces by non-native designers, with and – in some cases – without native feedback.

A final caveat: in Reading type design students develop native- and non-native script skills in parallel. This makes for better, deeper education, but is a different scenario from that of an already experienced designer of (for example) Latin typefaces seeking to learn how to design in another script.

Will there be another, new Erik Spiekermann? Or is time up for big stars like him?

This is a nonsense question. Erik is very successful in his field, with a high public profile – but the same can be said of many professionals in their respective fields. It is more appropriate to ask why is Erik’s success interesting, or whether his career is more revealing in relation to other high profile designers of his generation (of which, let’s be clear, there are many).

Erik’s career is notable for two reasons: firstly because, unlike other designers whose work is focused within a relatively narrow domain (such as typefaces, or posters, or transport maps, or branding) his work spans several domains: all of the ones I just mentioned, and then some. This richness of practice is illuminating in itself, regardless form the fact that in some of these cases it can be described as capturing the spirit of the times perfectly, and in a few cases even being ahead of the curve. There is a problem in this richness for those who want to capture design outputs into neat narratives, because clearly in Erik’s case there isn’t one, but multiple strands of thinking in parallel. So, the uniqueness of his work lies not in individual projects, but in the totality of his work.

The second reason Erik’s career is notable is that he has made a point of using his visibility to get key messages about design to wider audiences, and not just in the design world. Even in his most indulgent moments, the notions of rigour and process are present. He has also shown that user-sensitive, evidence-driven design does not need to be dry or visually uninspiring – a common failing in the wide information design world. And, related to this, Erik does not take himself seriously – one of the most positive personality traits one can aim for.

The second question (“is it time up for big stars”) neglects the length of Erik’s career. There are many people in the wider design world who are gradually building very strong public personas that can be expected to be just as recognisable and influential when they reach Erik’s age (and probably, give the speed with which things happen nowadays, much sooner). They are more likely to be from the “design for screens” crown (I want to avoid separating IA, UX, and so on) but there are many possible candidates.