Here is a short list of references for students beginning to work on Greek. It is not exhaustive by any measure, only a starting point. I list some historical texts, for the necessary grounding in the development of the [typographic] script, and some typefaces that are good examples of practice. (Don’t get all worked up about the typefaces on the list: each one listed may have unresolved issues, just as many good ones may not be listed. This is, after all, an introductory list. Also, I only include work I know in detail.) All texts are in English. (For MATD students: all items exist in the University Library, or the Department Reading Room, and in my office.)

Manuscripts and writing

Books with manuscripts and images of rare books might be good; there are some truly comprehensive editions of Greek manuscripts (like Greek literary hands by C H Roberts, in two volumes, and Repertorium der griechishen Kopisten, in three volumes. It is important to get a feeling for Greek writing, as it is (and was) done on entirely different models than western writing. In short, the the arm rotates freely, and the nibs (when not round) are cut with an opposite bias. If the titles above are not available, look up sources on Byzantine scribes. (But note: if you do general searches online, you must focus on secular or less formal documents, rather than the very ornate manuscripts of the Empire.)

As with all unfamiliar scripts, doing some writing exercises is essential to understand the entry and exit strokes, and the structure of the letterforms. I have included two sheets for practice in a zipped archive; use a pencil or other “direction-agnostic” tool when starting with writing exercises.

Typographic history

Victor Scholderer’s Greek printing types 1465–1927 catalogue is a good historical introduction. It stops in 1927, and has a specific bias. Scholderer outlines helpfully the three early strands of Greek typeface “design”: the upright joined style of Zacharias Kalliergis, the eventually dominant Aldine style, and the short-lived Complutensian. (I put “design” in quotes since “typemaking” would be more appropriate term. Our current interpretation of “design” implies a level of deliberation an reflection that did not apply at the time.) There is a somewhat rare original (500 copies only, grab one if you find it on sale) and a reprint from 2004 or so, with new essays by John Bowman and Martin Davies added. (Oak Knoll sells it in the US, and independent booksellers elsewhere.) The original has some exceptional reproductions in collotype, worth the price of purchase alone.

If you read this you can safely skip Robert Proctor’s The printing of Greek in the fifteenth century (1900), the other key text for early Greek printing, which is also more limited in coverage. (If interested, you can get a free PDF of Proctor’s book.)

H. D. L. Vervliet had published significant texts on the history of Greek typefaces. The Journal of the Printing Historical Society has two relevant articles: “Greek printing types of the French Renaissance: the ‘grecs du roy’ and their successors” (in new series no 2, 2000) and “The Greek typefaces of the early French Renaissance” (in New Series no 4, 2002).

John Bowman’s Greek printing types in Britain: from the late eighteenth to the early twentieth century is based on his PhD (Reading, 1988). It is interesting in its totality, but has an invaluable second chapter where forms from different typefaces are compared. It is published by Typofilia, and should be available to order via independent booksellers.

Michael Macrakis’s Greek Letters: from tablets to pixels has some articles that are very useful, and a few that are not very helpful, or under-researched. Some are out of date. But John Bowman and John Lane’s are essential reading.

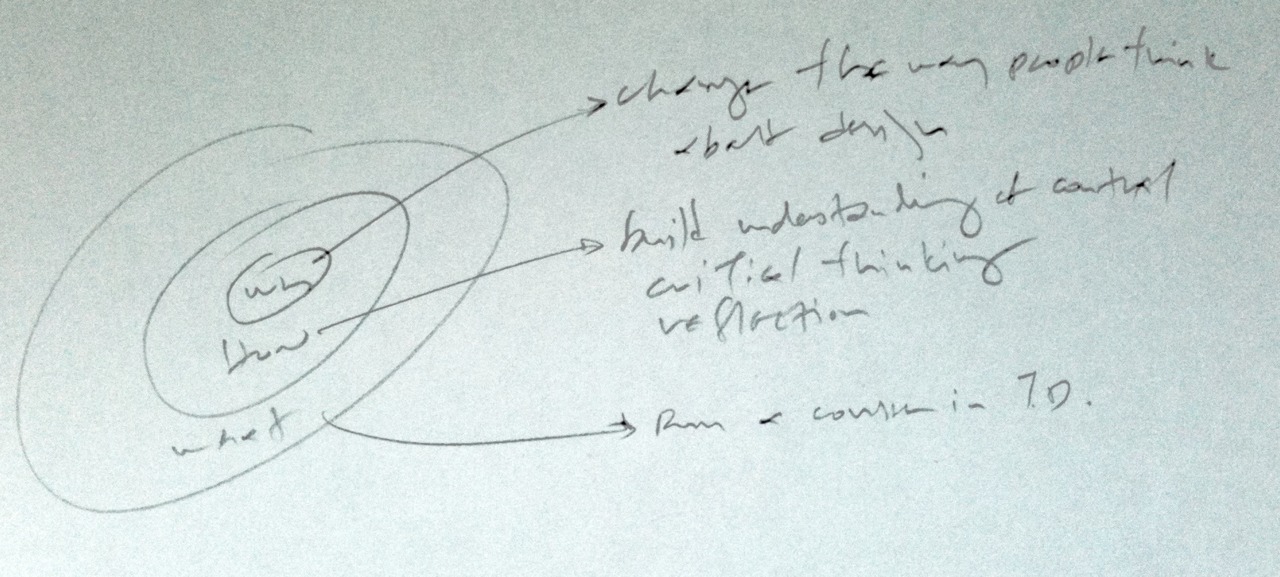

I wrote an article in Language, Culture, Type (ed. John D Berry, ATypI/Graphis 2002) with some basic ideas on the development of Greek typeface design. Also, I posted a couple of short texts on Typophile, one in a thread on Garamond Premier Pro encapsulating the history of Greek typefaces, and one on Greek scripts that comments on the model that designers need to have in mind.

There are also some useful comments on parallel script development in the booklet produced by Microsoft to document the development of the ClearType typefaces, Now read this (2003). According to a recent Typophile thread, it may eventually be available as a PDF. Regardless, the typefaces are relatively easy to view, since they are available with Microsoft Office.

Typefaces to study

In addition to the historical examples illustrated in the publications above, it is worth studying good examples. My list below is not exhaustive, and is only focused on text-intensive typefaces.

– Start with the Didot Greeks, which defined the contemporary modulated-stroke style; and

– the Monotype hot metal monoline / low contrast Greeks, which were models for Greek adaptations of Latin sans serifs

I omit on purpose the first batch of phototypesetting Greek typefaces, which were intentionally “Latinised”. Contemporary digital typefaces to look at:

– the ClearType family: the Greeks in all are good enough, but Gary Munch’s Candara is a superb example of fresh thinking.

– Robert Slimbach’s modulated Greeks: Garamond Premiere Pro offers a re-interpretation of a historical standard; Arno Pro, a versatile update of a calligraphy-inspired family, and the relatively new Adobe Text Pro (which always makes me think “This is what Times Greek should look like!”).

– Jeremy Tankard’s Greek typefaces: his Bliss Pro (as well as the CT Corbel) are exemplary low-modulation Greeks.

– Frantisek Storm’s Anselm Sans Pro and Anselm Serif Pro show a successful adaptation of Greek to a very eclectic style.

– Peter Bilak’s Fedra Greeks (the family is massive, and in the serif styles I strongly prefer Serif B over A). The extensive weights and styles of Fedra have made it extremely popular within Greece in recent years, mostly in newspapers and magazines.

– Hoefler & Frere-Jones’ Whitney Greek, a very good example of a Greek extension to a successful Latin family

Last but not least, John Hudson’s SBL Greek is probably the best updating of the traditional Didot style, with a twist. It has a massive character set, but unfortunately only one weight. It is a free download from the SBL site.

There have been some very good custom jobs, like the Vodafone Greek corporate typeface done a few years back by DaltonMaag (unfortunately the site does not show the Greek portion of the job) and the localised Cheltenham for the Greek edition of the New York Times (not easily seen online, if you don’t know Greek). Others are similarly difficult to see.

Student typefaces

Some very good Greek typefaces have been designed by students at the MATD. Here’s a small selection:

– Ben Jones’ Emrys (2011), an interpretation of a low-contrast style with an incised feel.

Toshi Omagari’s Marco (2011), a contemporary modulated style.

– Riccardo De Franceschi’s Ginnasio (2010), a typeface for reference editions.

– Alice Savoie’s Capucine (2007), a novel style reminiscent of a modulated brush stroke. The typeface is now published commercially by Process Type Foundry.

Postscript: letter grouping

If you are starting to design Greek letters, it is good to avoid the alphabetic sequence. A good basic set to begin with is alpha / epsilon / eta / iota / mu / rho (α, ε, η, ι, μ, ρ) which give a structure to the main counters, and some form to instrokes and outstrokes. This sequence will also allow many typical test words, such as είμαι, αίμα, ηρεμία, άρμη, ρήμα, ημέρα, ερημιά.

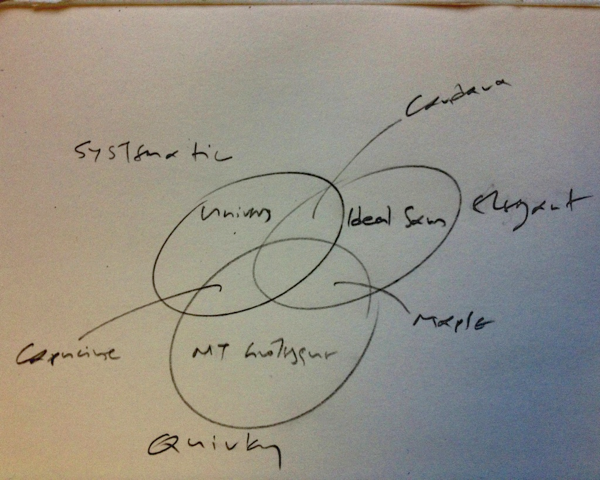

Try to group letters by their features. Here’s one grouping:

αδορσυωφβθ ες ηιμ γνχλ ζξ κ πτ ψ[φ long]

And another (with thanks to IV):

αηιμυ ψφ βδεθορσω πτ ζξς γκλνχ